Following the collapse of crude oil prices in 2018, which triggered unpleasant memories of the 2014 and 2015 crash in world oil prices, the Nigerian government found itself in unchartered waters. It continues to struggle to revive the economy amidst dwindling oil revenues compounded by unemployment, poverty and insurgency.

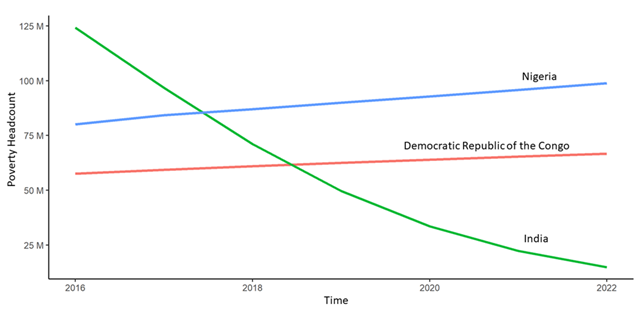

Global poverty projections released by The Brookings Institution in 2018, based on data from the World Poverty Clock, shows that Nigeria has overtaken India as home to the largest population of people living in extreme poverty, with 87 million citizens living on less than $1.90 a daycompared to India’s 73 million (see the graph below).

Based on the recent world poverty projections, the signs of Nigeria’s leadership failures are now even more glaring as nearly one hundred million Nigerians are in danger of falling into extreme poverty by 2022. This startling revelation implies that despite being the largest oil producer in Africa, Nigeria is unable to translate its oil wealth into rising living standards for its growing population.

Transformations in the global political economy following the fall of crude oil prices in 2018 crash, further accentuated Nigeria’s governance challenges. The situation seems compounded by the fact that Nigeria’s 8.6 trillion budget was based on a conservative estimate of the world oil price using a $60 per barrel benchmark at a time the price of oil at the international market was $75 per barrel. Although the price later escalated to $86 per barrel, it began a downward trend in the last quarter of 2018, closing at a year low of $59 per barrel. At the same time, current oil production in Nigeria is 2.1 million barrels per day, below the budget projection of 2.3 million barrels per day. Besides, the major oil multinational corporations operating in Nigeria have been cutting back their operations for a variety of market, security, and political concerns.

Arguably, the collapse of oil prices over the years not only pose a strategic danger to the country’s growing importance in the global economy but has been the new catalyst behind its domestic predicaments. For example, Nigeria’s forex market is responding negatively to the recent fall in oil prices as the local currency has dropped from the 363 naira per US dollar that it traded for a better part of 2018 to 370 naira per dollar. Should the fall in oil prices be sustained, it could lead to a shortage of the US dollar in the domestic market, further driving down the value of the naira.

The far-reaching implication is that changes in the price of oil have the potential to instigate changes in domestic conditions, which can lead to protracted instability.

Origins of dependency

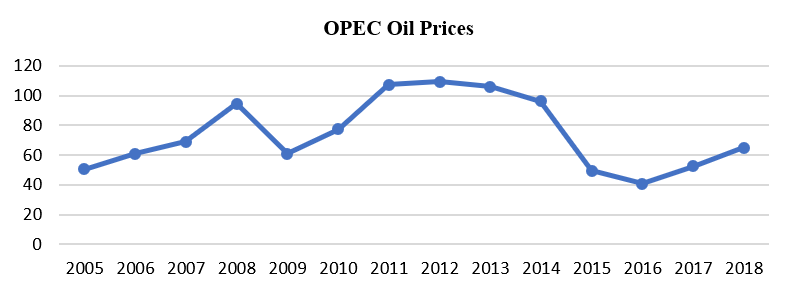

Nigeria’s predicament began with the OPEC crisis of the early 1970s, which led to significant changes in the world oil market as the price of crude oil skyrocketed from $3 per barrel to $12 per barrel in 1974. In the wake of the oil boom, the Iranian revolution of 1979, and subsequently the Iraq-Iran war that began in 1980 both contributed in further increasing the price of crude oil from a $14 per barrel in 1979 to $35 per barrel in 1981.

The most provocative policy of the Nigerian government was the dependence on oil resources as a source of foreign exchange earnings to the detriment of agriculture. However, the collapse of oil prices in 1986 produced severe consequence such as a shift in the global economy that triggered a crash of the stock market, soaring inflation, and high unemployment rate in Nigeria. By implication, the dependence on oil revenue to finance national development has made the Nigerian economy highly susceptible to oil price volatility.

Following the decline in oil revenues in 2015, the Nigerian government was forced to seek economic diversification and has identified agriculture as one of its key goals to help address the country’s dependence on food imports. There has also been significant progress in the Telecoms industry which seems to carry the weight of employment in Nigeria.

A report from the National Bureau of Statistics shows that Nigeria’s economy grew 1.81 percent in the third quarter of 2018. In the quarter under review, Nigeria recorded an average daily oil production of 1.94 million barrels per day, lower than the average daily output of 2.2 million barrels per day. The oil sector contributed 9.38 percent to real GDP in the third quarter of 2018, while the non-oil sector added 90.62 percent. The non-oil sector grew by 2.32% during the third quarter, driven mainly by the Telecoms industry, in addition to agriculture, manufacturing, Trade, Transportation and Storage, as well as Professional, Scientific and Technical Services. Despite the rhetoric on economic diversification, crude oil still accounts for an 81.1 percent share in Nigeria’s total exports.

Arguably, the growth in the non-oil sector has not translated to improvements in the living standard of Nigerians due to high unemployment rates. For example, data from the National Bureau of Statistics show that the total number of Nigerians classified as unemployed, meaning they have no job at all or worked less than 20 hours a week, increased from 17.6 million in the fourth quarter of 2017 to 20.9 million in the third quarter of 2018. Also, the national unemployment rate rose from 18.8 percent in the third quarter of 2017 to 23.1 percent in the third quarter of 2018. When compared against the 87 million Nigerians living on less than $1.90 a day according to The Brookings Institution’s report, the evidence is overwhelming that millions of Nigerians are living in extreme poverty.

Impact of oil dependency

Nigeria’s transition to democratic rule in 1999 produced mixed reactions as it emboldened ethnic grievances and gave impetus to the expression of minority rights which were previously reprised by dictators. Consequently, the threat of insurgency in the Niger Delta cut Nigeria’s oil production by 650 barrels per day by the end of 2008.

Nigeria experienced its lowest oil production output in 2015 following President Muhammadu Buhari’s decision to terminate the peacebuilding program initiated by the previous governments to deal with conflict in the oil region. The regeneration of insurgency in February 2016 caused a 50% shut down of crude oil production by May 2016. This period also coincided with the fall of crude oil prices from US$50 in 2015 to $US40 by 2016 as shown in the graph below. The loss of export revenue due to falling oil prices meant that the government would have difficulty financing development programs.

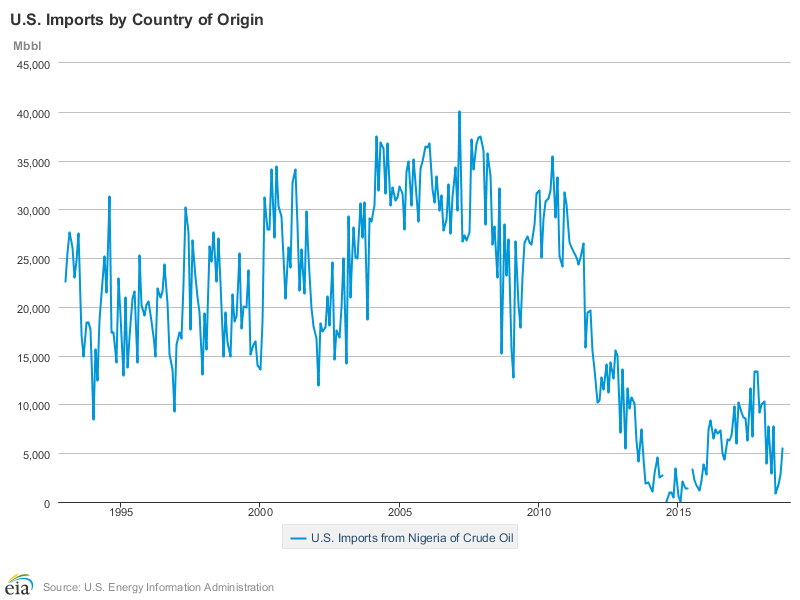

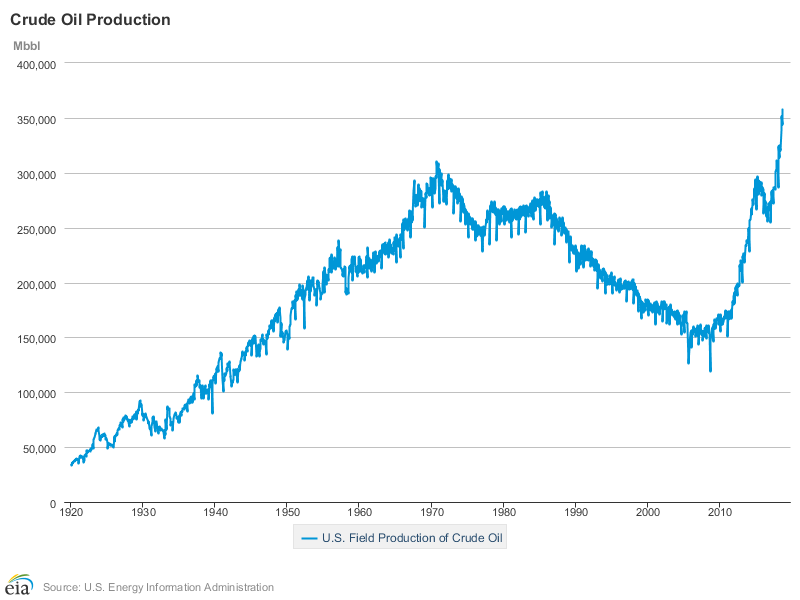

Analysts have attributed the collapse of oil prices to surging global supply driven mainly by the hydraulic fracking revolution in North America. Hydraulic fracking is an innovative well-simulated and environmentally friendly drilling technique that makes it possible to extract natural gas from shale, which was once impossible with conventional drilling technologies. As the graph below shows, Nigeria has experienced a significant drop in its crude oil exports to the U.S. as domestic production rises in America following the fracking revolution. There are growing concerns that shale production has the potential to drive down the price of crude oil, which will plunge Nigeria in a macroeconomic crisis.

As U.S. crude oil imports from Nigeria continues to decline, Nigeria may have to keep depending on external borrowing to fund its federal budget. What seems significant about this paradox is that oil price volatility has the potential to threaten Nigeria’s fragile democracy should it continue to have full sway over the economy.

Conclusion

Nigeria is facing severe governance challenges. Oil price volatility is accentuated by rising commodity prices, the devaluation of the naira against the U.S. dollar, and the effect of poor economic performances on unemployment, poverty, crime, and insecurity. These challenges have altogether altered the social fabric. Nigeria can break from oil dependency and emerge as a progressive society through innovation in governance.

Recommendations

1. Modernise the Agricultural Sector

One recommendation for addressing the resource curse is agricultural modernisation. In many rural communities, agriculture is still traditional. This challenge thrives due to the lack of modern technologies, access to information on crops, weather conditions, credit facilities and market opportunities as well as poor education. Innovation in the agricultural sector should serve to empower farmers by making technology, information and credit accessible.

Maximising the potential of the agricultural sector involves developing infrastructure, such as roads and efficient rail transportation systems to break the rural-urban divide that often prevents rural farmers from accessing urban markets.

2. Develop the Tourism Industry

Nigeria is endowed with rich natural ecosystems and cultural diversity that could be harnessed to drive economic diversification. Following the Rose Revolution in 2003, the Republic of Georgia remodelled its economy with a focus on building a capitalist economy where tourism plays a vital role in economic transformation. The United Arab Emirates has demonstrated the impact of tourism development in national transformation. Dubai has transformed into a modern economy and an attractive investment haven engineered by tourism.

3. Promote Entrepreneurship

Transforming the resource curse requires the government to redefine its role in economic transformation and its strategic relationship with the business sector. Using entrepreneurship to drive economic diversification would require education reform. Education must be enterprise-oriented, such that inspire creativity and innovation. The government, in collaboration with the private sector, should create the incentives for students to turn creative ideas into inventions that have an enterprise value. Such reform would encourage young Nigerians to harness their entrepreneurial spirits and compete based on the power of their ideas rather than the monopoly of violence.

(Main image: George Osodi/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.