As the world continues to recover from the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, coping mechanisms such as increased use of virtual workspaces, online marketplaces and e-governance have become the norm. While this presents opportunities to revamp economies and streamline public service delivery, it may also heighten exposure to cybercrime.

In Africa, many countries have seen a rise in reports of digital threats and malicious cyber activities. The results include sabotaged public infrastructure, losses from digital fraud and illicit financial flows, and national security breaches involving espionage and intelligence theft by militant groups.

Addressing these vulnerabilities requires a greater commitment to cybersecurity. This requires enforceable policy safeguards, risk prevention and management approaches, along with technologies and infrastructure that can protect each country’s cyber environment, as well as individual and corporate end-user assets.

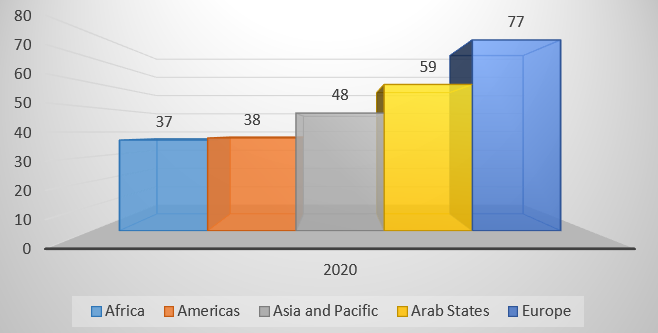

However, the latest Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI), released this June by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), suggests Africa’s levels of commitment to cybersecurity – as well as capacity for response to threats – remain low compared to other continents.

Africa’s cybersecurity gap

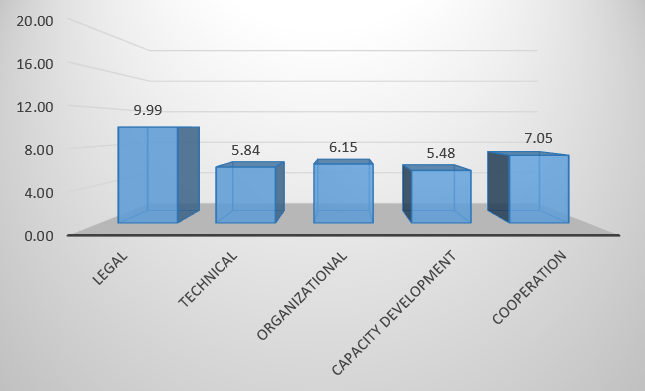

The GCI report examines the cybersecurity landscape in 194 countries by the end of 2020 and assesses their commitment to improving cybersecurity based on five pillars: legal, technical, organizational, capacity development, and cooperation. We highlight below the overall performance of African countries in line with these pillars:

- Legal: Out of 54 African countries assessed, 29 had passed legislation to promote cybersecurity. Four others are currently at the stage of drafting policies or seeking legislative approval. Africa comes second to Europe in terms of the prevalence of legislation. Of all the pillars assessed, this was the measure where the region recorded its best performance. Still, these legal frameworks lack adequate depth and breadth; only 17 African nations have adopted specific legislation to tackle online harassment.

- Technical: This measures the mechanisms and structures put in place at the national level to deal with cyber risks and incidents, and particularly the existence of a reliable Computer Incident and Emergency Response Team (CIRT or CERT). Out of 131 CIRTs identified across the globe, only 19 are in Africa, with an additional 2 in the pipeline. Interestingly, 6 of the 19 emerged between 2018 and 2020, reflecting a notable rise in a short period. Africa has only nine sector-specific CIRTs, set to respond to particular risks. This indicates a lack of maturity in the region’s cybersecurity measures.

- Organizational: This pillar examines whether coordination mechanisms are sustainable, if the roles and functions of implementing agencies are clearly defined, and possible actions to protect critical infrastructure. Based on this, only ten African countries possess a national cybersecurity strategy that fully addresses measures related to critical infrastructure. About the same number of countries have conducted an audit to track the progress of national cybersecurity efforts.

- Capacity development: All but six countries in Africa lack capacity-development incentives for cybersecurity – which aim to bridge the digital divide, build institutional knowledge, or address policy awareness limitations and skills shortages for cyber protection.

- Cooperation: Given that cyberthreats are borderless, countries need to embrace collaborative efforts on cybersecurity. As the GCI report reveals, just 19 African countries are signatories to multilateral cybersecurity agreements, in contrast to 41 European countries. Only ten African countries have entered into bilateral cybersecurity agreements.

Among the factors creating a conducive environment for cybercrime in Africa are limited public awareness and knowledge regarding the potential risks when using cyberspace, underdevelopment of digital infrastructure, limitations in institutional capacity to coordinate and implement available cybersecurity laws, and an absence of extensive cybersecurity policies. This implies room to improve the cybersecurity approach in African countries.

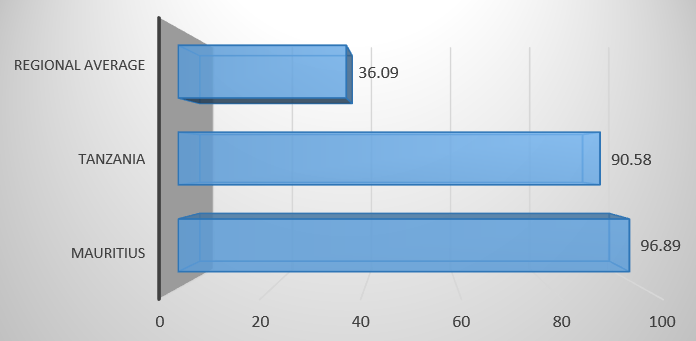

Model countries in the region

A few countries stand out as regional cybersecurity leaders. For example, Mauritius and Tanzania are top performers in the region in terms of GCI Indicators for 2020, with scores of 96.89 and 90.58 out of 100, respectively. Areas of strength for these sample countries include consistent investment in information technology infrastructure and skills, CERTs that also inform citizens on digital rights, and cross-border collaboration on cybersecurity initiatives. Other African countries could learn from this.

What next?

Our research at the Centre for the Study of the Economics of Africa (CSEA) highlights several ways to improve cybersecurity across the continent.

Specifically, decision-makers need to take the following actions:

- Increase public awareness campaigns to encourage behavioural change, such that Internet users are aware of possible cyberthreats and know to adopt preventive measures.

- Invest in building up cybersecurity capabilities and technologies to detect and mitigate cybercrime.

- Devote more resources to setting up and equipping CIRTs, ensuring adequate capacity to monitor and respond to incident reports.

- Legislate efficient procedures for investigating and prosecuting cybercrime, thereby to deter cybercriminals.

- Commit to enforcing robust legislation that governs cyber activities and protects digital rights.

- Where cybersecurity strategies are already in place, ensure better coordination and thus stronger implementation.

- Strengthen partnerships between domestic stakeholders – public and private – to encourage the sharing of intelligence on potential threats and collaboration to find lasting solutions.

- Enhance regional cooperation among African states to ensure a united voice when negotiating over multilateral cybersecurity standards.

- Adopt a collective, region-wide approach that encourages peer learning and knowledge exchange.

Note: The regional designations followed by CSEA are in line with African Union classifications. These differ from ITU regional designations in respect to the placement of some countries. Regional scores and observations may therefore deviate from ITU statistics and analysis.

Learn more about ITU’s regional presence.

This article was originally published on My ITU.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA.

(Main image: Getty Images )