Deploying peacekeeping missions in conflict-affected countries is one of the United Nations’ most distinct activities. In 2016 deployments reached a historic peak with approximately 120 000 civilian and military staff in the field in 15 missions and a budget close to $8 billion. At no other point in history have we seen the deployment of so many staff and missions, most of which are based in Africa. The UN currently operates in the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, Liberia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ivory Coast, Sudan, South Sudan and Western Sahara. In addition, regional organisations continue to deploy their own operations.

With peacekeeping being the tool of choice for the international community to address violent conflict, two key questions emerge: How effective are these missions and do they reduce levels of violence?

The answer is complex. Increasingly, peacekeepers are sent to countries in which there is no peace to keep (i.e. no reliable peace agreement exists). In countries like the CAR, DRC, Mali, Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan, violent conflict persists despite the deployment of large peacekeeping missions. Rebel groups, insurgents, local militias or Islamic terrorists are a serious challenge for international peacekeeping.

When evaluating how effective missions are, research has mostly explored the number of battle-related deaths during a peacekeeping operation. However, violent death might be a poor indicator if other forms of non-lethal violence as rape, riots or domestic unrest are not accounted for. Increasingly we have access to more sophisticated data which allows us to draw a different picture.

In a recent study aimed at determining whether UN mission deployments leave a positive imprint, my colleague and I applied a number of indicators such as battle death, violence against civilians, domestic unrest, national and personal security, accountability and the rule of law. We focused on larger missions deployed to Africa since 2000. There were 10 of these in Burundi, CAR, the DRC, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan.

The following graphs display average numbers of these peacekeeping missions.

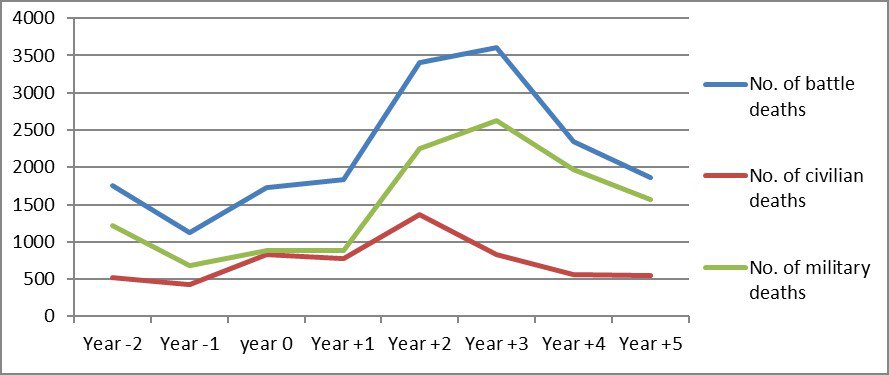

Figure 1: Average number of casualties per peacekeeping missions

One of the most important indicators for peace is the number of fatalities during armed conflict. In Figure 1 we can see that after the deployment of a mission (zero year), the death toll is actually increasing. A positive trend only takes effect after three years but even after five years the number of fatalities has not returned to pre-deployment levels. While peacekeepers are deployed, conflict does not immediately abate.

A more positive picture emerges when looking at the number of civilian deaths. While it also increases in the first two years, it falls quickly and sustainably thereafter. The delayed effect of peacekeeping missions should not be a surprise as it takes time to reach the mandated troop size. In addition, missions are often deployed in active war zones and encounter peace spoilers such as rebel groups, insurgents or terrorist groups.

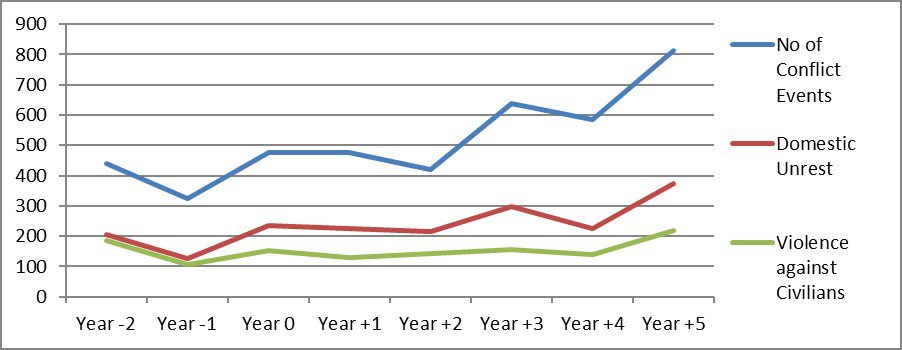

Besides battle deaths, do other forms of violence also decline? Here the answer is less positive. Using the data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) and calculating the average number of conflict events (lethal and non-lethal) as well as accounting for domestic unrest and violence against civilians, we can clearly see that violence broadly defined does not disappear but tends to increase (Figure 2). While peacekeeping missions reduce the number of battle deaths, after some time other forms of non-lethal violence seem not to be affected by mission deployments.

Figure 2: Average number of conflict events, domestic unrest and violence against civilians

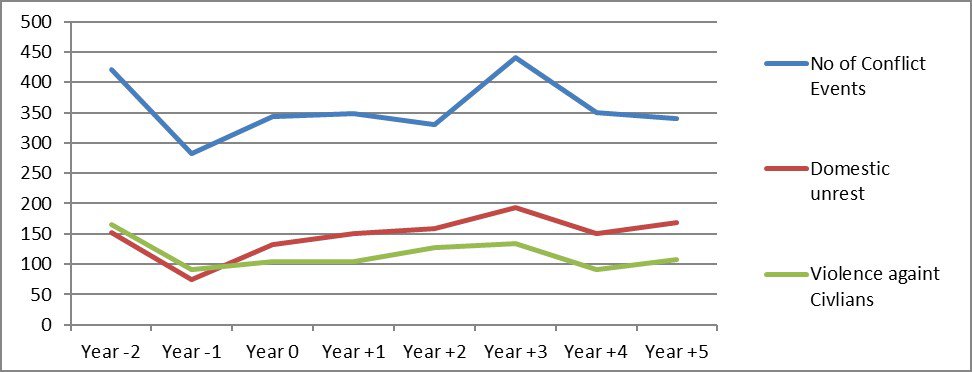

Given the small sample, individual cases can have an overly large impact on average numbers. This is the case with Somalia, which some argue does not fit into the general pattern of peacekeeping missions as its main mandate consists of actively fighting against al-Shabaab. Indeed if we exclude Somalia, the picture changes (only in these indicators). The number of conflict events, acts of violence against civilians and domestic unrest do not increase but remain stable (Figure 3). Thus while peacekeeping does reduce the number of battle death, other forms of violence persist and in the case of Somalia they increase significantly.

Figure 3: Average number of conflicts, domestic unrest and violence against civilians without Somalia

In this context it is worth noting that in most peacekeeping missions the civilian and police components are significantly smaller than the number of soldiers. The former often only make up some 20% of all staff. Soldiers are not always best prepared to address public order questions nor can the UN realistically be a substitute for national security structures. Still, strengthening the civilian component is essential. The UN should consider a more active role for its police officers by tasking them not only with monitoring and training national forces but also with engaging in active policing if necessary, at least in the first years of deployment and until domestic institutions can take over.

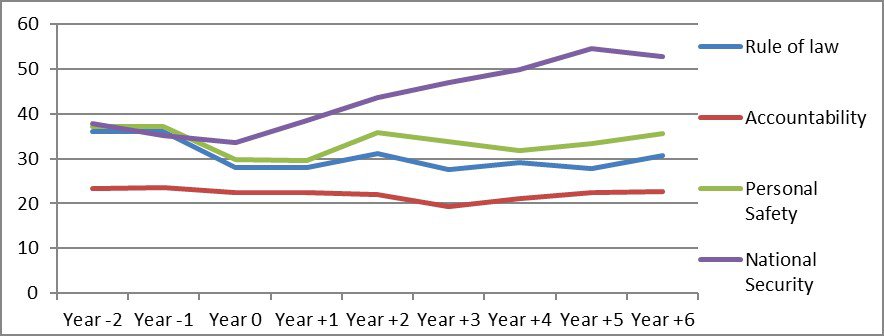

When using data from the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) we can observe a similar trend as just described (Figure 3). While the score for national security (state security, government involvement in conflict) develops positively with mission deployment, the indicator for personal safety (human security) only changes minimally. The de facto gap between state security and safety for the broader population widens the longer missions are deployed. Such a situation, if continuing, might nurture future conflict, complicate peace building and undermine the public legitimacy of international peacekeeping missions with the local population.

Figure 4: Personal and national safety, accountability and rule of law

Reducing non-lethal forms of domestic violence is also linked to post-conflict countries being able to provide for public order. Thus are there accountable security forces operating according to the rule of law? Unfortunately governance indicators on accountability and rule of law are not changing significantly with the deployment of a peacekeeping mission (Figure 4). There seems to be no immediate or mid-term positive effect measurable. Naturally, state and institutional building takes time (rather decades than years) and might not be fully realised while peacekeepers are on the ground.

In sum, do peacekeepers bring peace? When we focus more narrowly on negative peace or the absence of lethal violence, peacekeeping missions are able to bring down the number of battle deaths after some time. This is not trivial and should be seen as a major achievement of the international community. However, if peace is understood more broadly as positive peace, including indicators for personal safety or domestic unrest, then peacekeeping missions still have a long way to go to build a peaceful society.

Addressing public order questions is a far more complex and a long-term mission than sending soldiers to monitor a ceasefire agreement, demobilise rebels or patrol the streets. Non-lethal violence is best addressed through building effective institutions that uphold the rule of law. This requires long-term commitment long after a conflict has ended. Still, the current trend of deploying peacekeepers in active combat zones undermines the very prospects of building such institutions. In the short-term, strengthening the civilian and police component of missions is the best way to start this process as early as possible.

This analysis is based on a journal article entitled ”What peacekeeping leaves behind: evaluating the effects of multi-dimensional peace operations in Africa”. Read it here.

(Main image: Flickr/UN Photo/Stuart Price)