“The future promise of any nation can be directly measured by the present prospects of its youth.” These words, from former US president John F. Kennedy in early 1963, were intended as a call to action to address a challenge in the America of his day: a burgeoning population of young people were facing elevated unemployment and the troubling possibility of exclusion from the optimistic promise of their society. On International Youth Day, it is a call that resonates today, and most audibly in Africa.

Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, is home to the world’s most rapidly growing population. Currently at 1.2 billion people, its population will reach 1.7 billion by 2030, and more than double to 2.5 billion by 2050. It is also the world’s youngest population, which is in turn driving an expanding youth population. Estimates by the United Nations (UN) Population Division put the continent’s ‘youth’ (by the UN’s definition, those aged between 15 and 24) at just short of 231 million people, or 19% of the total – in tandem with broader population growth, they could reach 335 million by 2030 and 461 million by 2050. In African Union (AU) terms, these numbers are an understatement, since the African Youth Charter defines youth as those between 15 and 35, putting 420 million people – a third of Africa’s population – into the youth column.

Properly managed, population growth, with a sizeable ‘youth bulge’, can be an asset for development. Large numbers of young entrants to the labour market – with fewer dependents than older members of society – stand to boost per capita output, generating additional resources for consumption, saving and investment. This is what South Africa’s National Development Plan termed a “sweet spot” for economic acceleration, and was intrinsic to the economic transformation of East Asia in the last half century.

“The benefits associated with the ‘demographic dividend’ are not something certain and automatic. It needs to be earned with applications of proper policy mixes.”

But this is a possibility, not an inevitability. The wave of instability that shook North Africa and the Middle East between 2010 and 2012 owed much to an outburst of youth frustration arising from governments’ failure to meet young people’s aspirations. Ethiopian scholar Dr Admassu Tesso Huluka cautions: “The benefits associated with the ‘demographic dividend’ are not something certain and automatic. It needs to be earned with applications of proper policy mixes.”

The need for youth policies

Youth policies are a key response to this – so much so that the African Youth Charter and the AU’s 2009-2018 Plan of Action both stress the importance of instituting an appropriate policy framework (‘youth policies’) and supporting institutions to implement it. They attempt to integrate interventions in various fields to make a measurable difference on a society’s youth.

Emmanuel Edudzie of the Ghanaian non-governmental organisation Youth Empowerment Synergies explains:

“A national youth policy is a practical demonstration that youth are a priority, a declaration for youth development, a vision statement, a framework for political action, and a blueprint of the status, rights, responsibilities and roles of youth. When well done, a national youth policy can empower, enable and encourage youth, and maximise youth participation. Such policy can also provide realistic guidelines, timetable and framework for government, private sector and other stakeholders to work together to help youth, and ensure stronger coordination among youth-serving organisations and enhance service delivery.”

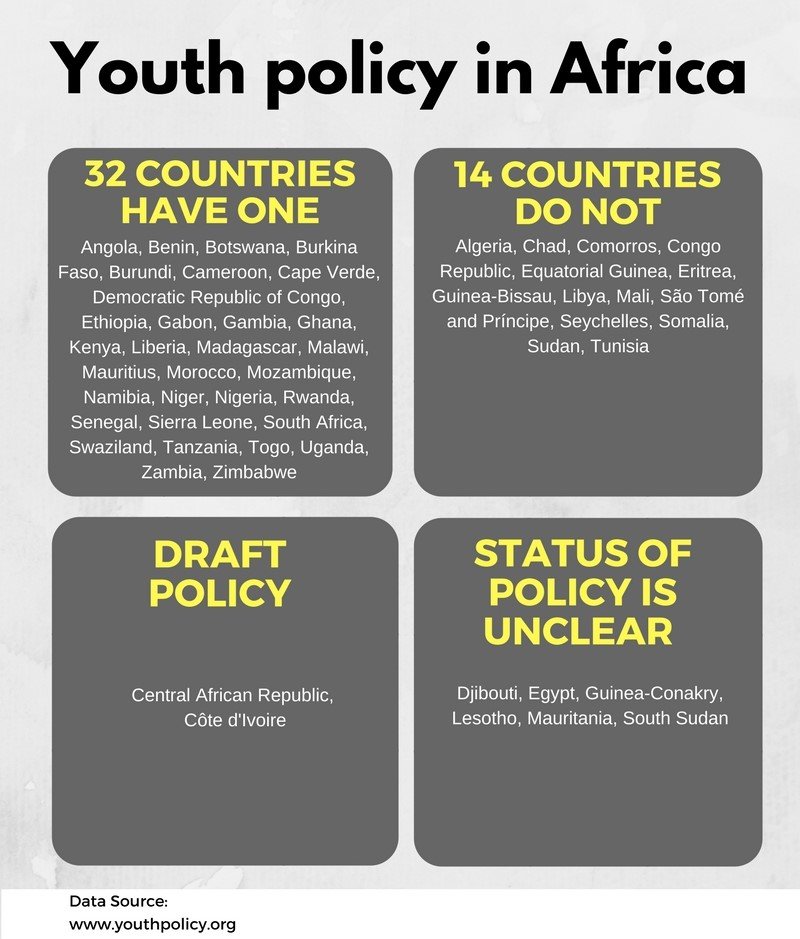

Youth policies are now common in Africa. Of the 54 countries on the continent monitored by the think tank youthpolicy.org, 32 have a youth policy, while two have one in draft form – just short of two thirds of the continent’s countries. In a further 14 countries, no youth policies exist, and in the remaining six, the status is unclear.

Youth policies seek to create the circumstances in which young people can fulfil their potential and integrate into the broader adult society as responsible, productive citizens. Indeed, if this objective is not met, countries’ very stability could be imperilled. One reason that the AU defines youth as the extended period between 15 and 35 is to reflect the difficulty that young people experience in establishing themselves in this way. For many, their lot is a disconcerting ‘waithood’, during which they cannot assume the full responsibilities of adulthood despite being ready (even expected) to do so. The reports of the African Peer Review Mechanism have identified the consequences of this: alienation, crime, drug abuse and promiscuity, as well as a willingness to follow charismatic leaders and provide the ‘muscle’ that sustains conflict.

Each to their own

Youth policies encompass an array of strategies whose remit is limited only by the analyses of the governments in question and their ambitions. Each country’s policy will attempt to address its own set of issues – Botswana’s seeks intergenerational understanding along with moral and spiritual development of its youth, while Ethiopia’s youth policy aspires to empowering youth to participate in globalisation processes.

But several notable common themes stand out. One focus of African youth policies is education. “Education and skills training,” remarks Ghana’s youth policy document, “are critical to the development of a young person’s productive and responsible life.” This is a defining issue for the continent: educational challenges range from basic literacy through vocational training to the advanced studies that are necessary for economic innovation. Meanwhile, the education provided (sometimes at great cost to both the fiscus and the individuals concerned) is frequently deficient in its quality, and fails to match the demands of the existing economy.

Dealing with these problems typically requires a sweep of interventions. Kenya’s youth policy is emblematic, pledging 19 distinct strategies (among other things) including curriculum reform, bursaries, upgrading facilities, linking training institutions’ offerings to market needs and encouraging partnerships with stakeholders outside government. Mauritius’s youth policy adds a distinct goal of capitalising on informal, lifelong learning, encouraging young people to improve themselves.

“Botswana seeks intergenerational understanding along with moral and spiritual development of its youth, while Ethiopia’s youth policy aspires to empowering youth to participate in globalisation processes.”

Socio-economic inclusion

Another focus is socio-economic inclusion – something which tends to primarily be conceived through economic participation. Above all else, giving young people an opportunity to earn a living is recognised as central to their prospects in society. (This is not merely about livelihood: as the American intellectual and politician Ben Sasse has argued persuasively, a sense of self-worth is conferred by being involved in productive activities.)

Employment promotion provisions in youth policies are diverse, in accordance with the intractability of the issue and lack of a clear consensus on how to address it. Malawi’s youth policy lists among its interventions measures to expand opportunities in the agricultural sector, information provision, regulatory reforms and education and training endeavours. South Africa’s youth policy draws attention to the 2013 Youth Employment Accord between business, labour and government – which aimed for collective action to draw young people into the economy – to the tax incentive offered to companies hiring young job seekers, to public works schemes and to measures to provide young people with exposure to working environments.

Along with employment, youth policies often seek to encourage entrepreneurship. Zambia, for example, emphasises this in its youth policy. It signals an intent to upscale existing programmes, providing capital, linking youth enterprises to larger firms, promoting cooperatives and developing entrepreneurial skills among the youth.

Works in progress

How successful these have been is a matter of debate. For the most part, these policies remain works in progress and determining whether outcomes – positive or negative – can be attributed to them is difficult. A significant amount of commentary has nevertheless drawn attention to their failings. As Professor Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong and the late Professor Mwangi Kimenyi argued in a paper for the US-based Brookings Institution: “Unfortunately, youth policies in Africa have fallen short of the massive challenges facing youth.”

A central hindrance has been the information gaps that characterise much of Africa’s policy environment. Evidence is frequently lacking about the precise nature of youth problems, compromising the quality of programmes. Monitoring and evaluating systems are also weak, limiting the ability to adapt them over time. The resources and capacities available to most African countries are not equal to the scale of the needs. Thus, initiatives to fund youth enterprises run up against the limited envelope available to them – and, as Kenyan policy specialist and youth advocate Raphael Obonyo has noted, in that country these are structured much like commercial loans, requiring collateral which most do not have.

Perhaps more important is the management and administration of youth policy. Much is made in published analyses of the need for an institution to coordinate and champion youth policy. Yet where high-level political support is missing, these may have to fight impossible battles against far more powerful interests. Conversely, as in Nigeria, the body responsible for youth policy may monopolise the implementation of efforts, steering resources into chosen initiatives and failing to build the social partnerships that could increase policy innovation and impact. In yet other cases, such as South Africa’s National Youth Development Agency, allegations of capture by political interests have damaged their reputation and ability to pilot a youth agenda.

The challenge of providing for Africa’s youth – or, perhaps more accurately, enabling it to provide for itself – is one that demands a response from government. But it calls for a smart, strategic response. Limited, achievable ambitions, backed by adequate resources and overseen by competent, committed administrative and political leadership are imperative. This must be complemented by partnerships with civil society, business and above all the youth themselves. Nothing less will elevate the present prospects and future promise of Africa’s youth – indeed, of Africa itself.

Read the Policy Briefing on which this article is based here.

(Main image: Getty/AFP/Aminu Abubakar)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.