The following article is part of a series on youth innovation during COVID-19 developed by the African Centre for the Study of the US at Wits University, the Youth Bridge Trust, and the Africa Portal.

The Covid-19 pandemic has unveiled the crippling inequalities that exist in African societies, where marginalised groups, particularly young women aged between 15 and 35 years, bear the brunt of fragility and disparity. This is social exclusion, arising from cultural perceptions, a lack of equal opportunities and barriers to learning and participation. This analysis provides a brief synopsis of the socio-economic issues affecting these women, seen through rising cases of gender-based violence and a widening gap in the digital divide. It further outlines the opportunity for Africa to redefine women’s youth participation that is anchored on inclusivity and skills-building.

Gender-based violence

The prevalence of gender-based violence in Africa has been a growing concern, even prior to the declaration of Covid-19 as a global pandemic and implementation of safety protocols such as nationwide lockdowns.

The New Partnership for Africa’s Development estimates that in Africa, nearly half (45.6%) of women and girls over 15 years have experienced physical or sexual violence. Furthermore, countries such as South Africa are ranked among the highest in terms of femicide, occupying the fourth worst position globally. 2014 government statistics from Kenya also indicate that some 45% of women and girls aged 15-49 years have been victims of gender-based violence and 20% of women aged 15-49 years have undergone female gender mutilation or circumcision. In Morocco, the prevalence of violence against women remains, where the most vulnerable are between the ages of 25 and 29.

In West Africa, President Julius Maada Bio of Sierra Leone in February 2020 even declared a national state of emergency on rape and gender-based violence. This decision was made in response to protests and campaigns that were sparked by a case of sexual assault of a young girl by a family member that resulted in her paralysis from the waist down. This incident follows the growing number of sexual assault cases in Sierra Leone, which are reported to have doubled from 4,750 in 2018, where 76% of the rape victims were below the age of 15, to 8,505 in 2019.

In the following month, the first case of Covid-19 was detected in Africa and reporting has shown that gender-based violence has increased substantially since the outbreak of the pandemic and with the subsequent lockdown protocols by individual countries. The African Union Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women, Lucy Asuagbor, has even expressed her concern in this regard.

This ‘shadow pandemic’ has taken centre-stage in South Africa. During his briefing on 17 June 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa provided scathing instances of gender-based violence and femicide in South Africa. “Over the past few weeks no fewer than 21 women and children have been murdered. Their killers thought they could silence them” said the president. Seven of the victims murdered were young women killed by men. Statistics show that there were approximately 5,000 cases of gender-based violence reported during the highest and second highest restriction levels in the country (levels 5 and 4) in Gauteng alone, between March and April 2020.

Elsewhere, a study led by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) found that gender-based violence has risen by 10% and sexual assault by 27% in the Central African Republic since the Covid-19 pandemic began.

The prevailing effects of the digital divide

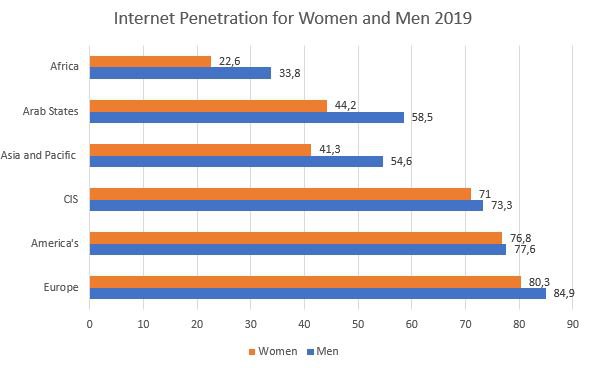

Another significant challenge facing young women during the pandemic is a lack of internet and ICT infrastructure access, including access to high-speed and stable internet, access to computers, and access to network coverage in remote/rural areas. While this problem is not unique to women – most recent data by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) shows that only 17.8% of Africans have internet access in their homes, while merely 10.7% have home-based computers – there is a clear gendered dimension to this lack of access to the internet, as illustrated in the graph below. Indeed, the digital divide across gender shows that there is a 11.2% gap between men and women regarding internet access. This enunciates the imperativeness of gendered interventions.

Furthermore, even where access to internet exists, data is not always affordable – serving as another exclusionary factor. South Africa is reported to be among the countries with the highest data prices along with Zimbabwe, Namibia, the Seychelles and Congo Brazzaville when compared to countries such as Nigeria, Tanzania, Rwanda and Egypt. Although the Competition Commission in South Africa ordered MTN and Vodacom to reduce their mobile data prices (resulting in a 33% reduction in data prices), the price of data remains expensive for the average person.

There are also deeper social and environmental impediments that make it difficult for marganalised groups – such as young women – to participate fully and effectively in online meetings and workshops. For example, even with access to the internet and ICT infrastructure, involvement may be hampered due to homes being shared with a large number of people, making it difficult to attain conducive spaces to participate online. Furthermore, there is the additional burden of housework, such as cooking and cleaning, on women.

Where to from here for marginalised young women?

Marginalisation of the youth – particularly young women – has resulted in their disenfranchisement and political apathy. However, this global pandemic has renewed the world’s appetite for innovation, inclusivity and new methodologies. Certainly, where there is crisis, there is opportunity. Herein lies an opportunity for us to help shape what policy participation looks like in a post Covid-19 era.

Young women should continue to increase their voices using social media and other relevant platforms and be part of agenda setting for a post-Covid-19 era. Albeit, this is contingent upon leaders and policy makers seeking out approaches that allow for inclusivity and abandon gatekeeping. Young women need to clearly articulate their needs, what works for them and what does not work. Interventions in this regard may require more accessible platforms in which young women can engage and share ideas not just among themselves but with leaders and government as well.

The UNICEF Youth Advocacy Guide can be cited as an example in this regard. This guide sought to build the skills of youth in advocacy and policy participation by looking at key aspects of advocacy (e.g. youth unemployment, gender-based violence, female gender mutilation, human rights, governance). It also includes information on research and fact finding, on reading and commenting on a policy document, on social media campaigns, on how to engage with stakeholders, and on monitoring and evaluation. It is noteworthy that this tool was co-created by Africa’s youth. These are the types of approaches that need to be scaled up for young women, taking into consideration the types of challenges and opportunities caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

It is also imperative that the continent leverages the widespread embrace of online alternatives while attending to matters of access and inclusion. “Migrating to digital platforms does not only present challenges and obstacles, there are some positive gains that are notable in that online platforms allow for organisations to increase the reach as opposed to physical contact,” observes Itumeleng Mphure, Programme Officer at Youth@SAIIA during an interview.

In the medium to long-term, there needs to be sufficient support for organisations and campaigns that seek to bridge the digital divide, particularly in remote and rural areas. These projects can be scaled up to create employment opportunities for youth and specifically young women, particularly as the International Labour Organisation projects that an estimated 22 million jobs will be lost in Africa in the second quarter of 2020 where more women may be adversely affected than men. In 2019, female unemployment for 52 African countries averaged 9.87% compared to 7.3% of male unemployment. The female unemployment rate in South Africa was 30.33% (26.39% for men), Algeria was 20.08% (9.70% for men), Senegal was 7.45% (6.03% for men) and Ethiopia was 2.76% (1.49% for men).

In addition, more financial support and resources need to be availed for the creation of jobs and to support advocacy that is geared towards further lowering data prices, particularly as students and organisations increasingly rely on online alternatives. This also calls for the strengthening of public-private sector partnerships for investment in and regulation of quality broadband infrastructure that provides stable and affordable high-speed internet that can be accessed in remote areas ensuring inclusivity.

Concluding remarks

The issues that have been outlined in this piece, notably – gender-based violence and the digital divide for women – demonstrate the need for inclusive, action-oriented interventions that endeavour in their approach to leave no one behind. These are matters that are at risk of being exacerbated further should adequate policies and recovery plans not be in place. As leaders find new approaches in this new normal, marganalised young women should leverage this to place issues that affect them on the agenda, propose solutions and demand inclusivity.

(Main image: Double exposure of a young African woman over an African landscape at sunset and Nairobi skyline. – Getty Images)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.