What is the Cotonou Partnership Agreement (CPA)?

Signed in June 2000, the CPA is a treaty between the European Union (EU) and 79 African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries. Its main objectives are poverty reduction, sustainable development and economic integration of ACP countries into the global economy through development cooperation, political cooperation and economic and trade cooperation. The CPA has a strong mandate for political dialogue with a focus on fostering mutual understanding, facilitating consultations and strengthening cooperation between the parties. The CPA provides for flexible discussions to be held at national, regional or continental levels, within or outside the institutional framework, and includes participation from the Joint Parliamentary Assembly, central government agencies and civil society organisations.

The current CPA will expire in February 2020, and negotiations on a successor agreement are set to commence in September 2018, with the objective of adapting the partnership to frameworks like the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Accord. The negotiations will take place against the backdrop of changing geopolitics and shifting global alliances, which cast a shadow over the integrity of the ACP group.

How is the CPA funded?

The CPA is funded by direct contributions from EU members to the European Development Fund (EDF). The EDF lies outside the EU budget. Financing is provided either in the forms of loans from the investment facility (managed by the European Investment Bank) or the grant facility (managed by the European Commission).

The CPA’s development cooperation is tailored for the individual circumstances and developmental needs of each ACP member. This is achieved through implementation of mutually agreed upon Country/Regional Strategy Papers and national indicative programmes that prioritise activities and cooperation programmes within ACP countries. The purpose of programming is to ensure that EU development assistance is based on a recipient country’s own development objectives and strategies, while also accounting for joint ownership, mutual accountability and harmonisation with the recipient ACP country.

Historical origins: from Yaoundé to Lomé

The Rome Treaty, signed in 1957, established the European Economic Community (EEC). As a condition to signing the Treaty, France requested that the EEC establish reciprocal trade agreements with the African Associated States and Madagascar (AASM, all former French colonies) and support their developmental efforts.

This resulted in the 1963 and 1969 Yaoundé Agreements that formed the basis for cooperation between the newly independent African states and the EEC. The Yaoundé Agreements built on the Rome Treaty’s ultimate goal to expand trade and granted the EEC greater access to the AASM’s resources and markets. In comparison, many AASM countries remained overly dependent on the EU markets and continued to focus on exporting raw commodities and materials. The Yaoundé Agreements were also criticised for enabling France’s political and economic dominance in francophone Africa, which continues to this day. Nevertheless, the agreements provided both aid and trade access to the EU market on a reciprocal basis.

As a result of the United Kingdom joining the EEC in 1973, and in order to address the needs of the newly integrated African Commonwealth countries, a new generation of conventions (the Lomé Conventions) replaced the Yaoundé Agreements in 1975. Together with the addition of West African countries, they formed the ACP group that comprised 46 member states at the time.

Although the various Lomé treaties focused on furthering trade, investment and industrial development, they continued to reflect the dominant development ideas of the period: provision of public funds to invest in projects as a way to contribute towards the development of the recipient country. Lasting from 1975 until 2000, the Lomé Conventions I to IV were revised every five years and had far-reaching impact: for example, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund supported structural adjustment programmes in ACP countries as a tool to foster economic growth.

The Lomé Conventions are recognised for their innovative approach towards cooperation, which included (i) principles such as the equality of the partners and dialogue; (ii) contractually agreed-upon rights and obligations; and (iii) predictability of aid and joint administration of the cooperation. These are features that continue to shape the EU-ACP’s relationship even today. The Lomé Conventions also granted ACP countries unlimited entry to the EC market for 99% of industrial and other goods originating within the ACP group and provided for new, significant trade provisions exclusively in favour of the ACP group:

• A system of non-reciprocity that enabled positive discrimination in favour of the EU’s ex-colonies;

• Refining the rules of origin;

• Granting a special protocol to regulate sugar; and

• Providing special treatments for beef, rum and bananas.

However, the heavily preferential treatment in favour of ACP products resulted in a World Trade Organisation (WTO) dispute concerning the EU’s preferential banana regime, underscoring the Lomé Conventions’ incompatibility with WTO trade rules. Moreover, the Conventions had not succeeded in increasing ACP exports to the EU market: ACP countries’ share of the EU market had actually declined from 6.7% in 1976 to 2.8% 1998, and finally, to 1.3% in 2000.

The non-reciprocal provisions of the Lomé Conventions did not achieve improved trade for ACP countries nor diversification of exports, eliciting criticism for perpetuating a system of ‘collective clientelism’ that further entrenched African dependency on European markets and the export of raw commodities. As a result, they were replaced with the CPA in 2000, which sought to improve ACP ownership and move from trade preferences to economic cooperation, while prioritising political cooperation.

Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) in the CPA

Following the WTO dispute, the EU was given until 2007 to bring the Lomé Conventions within WTO rules. The EU Green Paper identified several options for trading arrangements after 2000, which included: (i) single trade arrangement versus multiple trade arrangements; (ii) differentiated versus generalized trade agreements; (iii) reciprocal versus non reciprocal trade agreements; and (iv) contractual (providing long-term security, bilateral or multilateral) versus unilateral (at EU political discretion).

The EU eventually decided that regional free trade areas (FTAs) would be the best option, giving rise to the EPAs. Opinions differ, but the EPAs are either seen as a tool to further development or a complication for ACP-EU relations. Designed to modernise EU-ACP trade relations, the EPAs were developed as a key element of the CPA to create FTAs between the EU and ACP countries, work towards the eradication of poverty, and improve the CPA’s compliance with WTO rules.

As developmental tools the EPAs were expected to achieve three key outcomes:

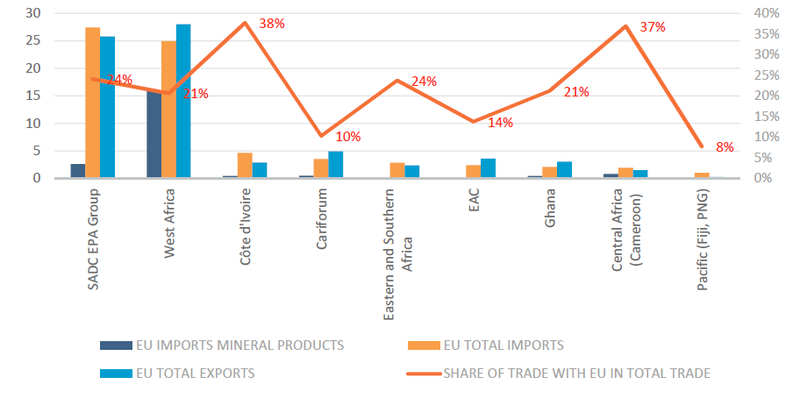

(i) Regional level agreements meant the EPAs would contribute towards deeper regional integration, facilitating the entry of ACP economies into the global economy and boosting trade and investment. From the EU’s perspective, the EU remains a major (and in some cases) the largest trading partner for ACP regional economic communities (see Figure 1 below).

(ii) Ensure indefinite, immediate and fully liberalised market access to the EU market for ACP goods and incrementally enabling ACP services’ access to the EU market, while at the same time providing gradual, reciprocal access to EU goods and services over a period of up to 25 years. This reflects a sharp departure from the Lomé Conventions, which were non-binding and non-reciprocal.

(iii) Ultimately shift ACP-EU relations away from an aid paradigm towards a new trade partnership.

Figure 1 – Trade in goods between the EU and EPA groups, billion euros (left) and % (right), 2017

(Source: European Parliament Briefing – An overview of the EU-ACP countries’ economic partnership agreements by Ionel Zamfir)

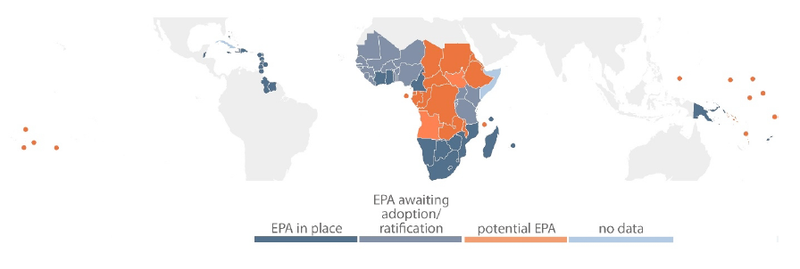

There are nine EPAs covering 51 ACP countries including those who have not signed up to an EPA but that are explicitly mentioned as parties. Seven regional EPAs have been concluded, of which four are considered final EPAs (West Africa EPA, the EAC, Cariforum and SADC) and three interim EPAs, which are expected to pave the way for more comprehensive EPAs.

Figure 2 – Coverage of ACP countries by EPAs with the EU, 2018

(Source: European Parliament Briefing – An overview of the EU-ACP countries’ economic partnership agreements by Ionel Zamfir)

To facilitate the EPA negotiations, the scope was predominantly reduced to trade in goods, with a commitment to negotiate services in the future. Only the Cariforum EPA includes services and other trade-related areas such as investment, competition and investment rights.

African countries were unhappy with the high rate of liberalisation required (80% market access to be granted to the EU), fearing that such a loss of policy space could impede their industrialisation efforts. The implementation of the EPAs amongst those RECs with members holding multiple REC memberships was viewed as detracting from regional integration efforts across Africa and complicating relations with partners outside the continent.

The EU has since agreed to remove its agricultural export subsidies, thereby creating a more even playing field for Africa’s agricultural goods. Furthermore, the EPAs also provide for more flexible rules of origin, which allow ACP countries to procure inputs from other countries in their exports and enabling better integration into global/regional value chains. Producers of the most sensitive 20% of goods also enjoy permanent protection from competition, and can apply safeguard measures to ensure that EU products do not compete against locally produced goods.

However, it is not a foregone conclusion that the EPAs will meaningfully contribute to economic development unless they are integrated into countries’ and regions’ own programmes and priorities – for example through reforms in trade facilitation that will enable the creation of regional value chains. Pending the finalisation of the outstanding EPAs, it is still too early to assess their true economic impact. Moreover, renegotiating the CPA will not reopen EPA negotiations either, which raises questions about the relevance of a future CPA.

Challenges facing the CPA

Since its formation, the ACP group has played a leading role in helping the EU maintain its relationship with its former colonies. The ACP Secretariat has played an important role in representing and speaking on behalf of much of the developing global South. However, stronger bilateral relations between the EU and the African Union (AU), coupled with initiatives such as the Joint Africa-EU Strategy and their close bilateral engagements have resulted in the EU preferring the AU as its institutional partner of choice for African affairs. The AU is slowly establishing itself as a key interlocutor in peace and security and continent-to-continent relations of a more political nature, which could undermine the ACP’s prominence.

At a meeting of the AU Executive Council in March this year, the AU indicated its desire to adopt a new cooperation agreement on the future of AU-EU relations post 2020 with the EU outside the ACP context. The ACP Parliamentary Assembly Declaration responded with a call for solidarity and a “desire not to take any position that will fragment the ACP group which will threaten the unity that is embedded in the values of the ACP group“.

On 14 September 2018 the AU will convene a Ministerial Council to discuss the Africa Common Position on its post-Cotonou relations with the EU, which may (or may not) translate into a concrete negotiating mandate. This reflects a clear tension within the ACP group that could, in the long term, prove to be a weakening force within the ACP.

Regional differentiation is a growing trend that reflects the formulation of specific EU support strategies for ACP countries. The EU has also taken a differential approach towards regional development, which is most notably reflected in the EPAs. For example, despite its aims for trade as a developmental tool, the EPAs have been criticised for not facilitating structural transformation of ACP economies and not benefiting those most affected by structural poverty. Political dialogue and trade within the CPA are de facto regionalised and some suggest that the ACP group has been reduced to managing and channelling development aid from the EDF to individual ACP countries for intra-ACP cooperation.

The CPA also does not provide detailed operational guidelines on how to structure dialogue processes, but rather opts for pragmatism and country-specific approaches. It is important that political dialogue should be ongoing, flexible and wide-ranging in its scope and context so that it can be used as a positive tool to address poverty or improve cooperation.

Although the European Commission has indicated that the CPA could potentially be extended beyond 2020, its looming expiry provides the ACP group and EU states with a chance to critically assess ACP-EU relations and the shape that future relations could take. In fact, the EU and the ACP group have agreed to postpone CPA negotiations until the outcome of the AU Ministerial Council is clear.

For a detailed analysis on the way forward and the EU and ACP group’s respective positions on the upcoming CPA negotiations, read Part II.

(Main image: Flickr/Malta in EU)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.