This article is published in partnership with the African Centre for the Study of the United States (ACSUS) at Wits University.

The microblogging website Twitter is the most commonly used social media platform by government officials, diplomats and world leaders to engage with the public, communicate policy and leverage their influence. This practice has come to be known as ‘twiplomacy’ – a term coined by public relations firm Burson-Marsteller in their studies, or hashtag (#) diplomacy. According to the US State Department definition, diplomacy is the art of enforcing and conducting negotiations, maintaining relations and resolving issues between nations without hostility and use of force. Digital diplomacy basically translates this concept through digital tools such as Twitter. This article examines reactions to the use of digital diplomacy on Twitter by the US Ambassador to Kenya, Kyle McCarter, and the late South African Ambassador to Denmark, Zindzi Mandela.

Twiplomacy in the African context

In order to understand twiplomacy in the African context, there is need to reflect on the challenge of internet access on the continent. According to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) 2019 report, 89.4 % of the population in Africa have mobile connectivity and 38% of the population in Africa are covered with at least an LTE/WiMAX mobile network. A further 79% of the population are covered by at least a 3G mobile network. Social media platforms in Africa are mostly accessed via mobile connectivity since internet connectivity in homes is relatively low. The ITU report states that 17.8% of African households have internet access at home. With this and the relatively high data costs in mind, citizens, diplomats and most foreign ministries in Africa have invested very little in digital diplomacy compared to their western counterparts.

The use of Twitter to complement traditional diplomatic efforts was popularised during Barack Obama’s US presidency. In their paper, Christine B. Williams and Girish J. Gulati suggest that Obama used Twitter extensively during his election campaign, while many credit his electoral victory to his savvy use of the platform. In 2015, Obama set up the official US Presidency Twitter handle @POTUS, which now has over 31 million followers. The account was inherited by Donald Trump after he was inaugurated as president in 2017, but Trump also tweets from his personal handle, @realDonaldTrump. In Africa, leaders such as Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and Rwandan President Paul Kagame have managed to draw huge followers on Twitter. Kenyatta uses the @StateHouseKenyaaccount which has drawn over 1 million followers, while Kagame’s handle, @PaulKagame, set up in 2009, has 2,1 million followers. The two East African leaders have led digital diplomatic efforts in Africa, prompting other African leaders to follow suit and become active on social media.

The use of social media in politics and diplomacy has come under the academic spotlight in recent years, particularly during Trump’s election campaign and after he assumed office. The @realDonaldTrump handle has over 86 million followers and has been the outlet for the president’s gobsmacking expressions of anti-immigration sentiment, fake news accusations, right-wing nationalist populism bordering on racism and climate change denial, as well as for peddling misinformation. Earlier this year, Twitter introduced fact check labels on Trump’s tweets about election fraud and this week blocked a post in which he falsely suggested that the flu was more deadly than COVID-19.

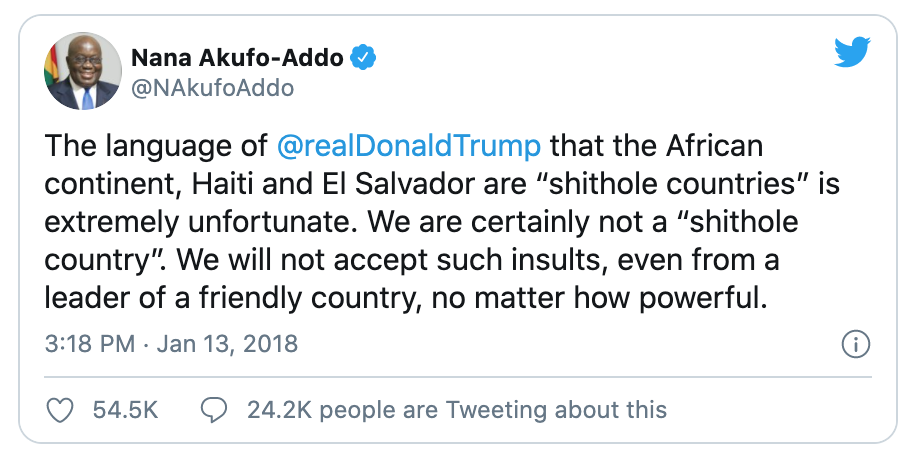

On a diplomatic relations front, Trump’s infamous labelling of African nations as “shithole countries” in 2018 stands out. It elicited stern responses from across Africa, including heads of state.

Among them was Ghana’s President Nana Akufo Addo, who tweeted:

The McCarter tweets

Kyle McCarter was appointed as the US Ambassador to Kenya by Trump in January 2019. He actively uses Twitter to propagate US policy in the East African country while building and maintaining relations between Kenya and the US. Below, I examine how he has actively used Twitter and hashtag diplomacy to achieve these specific goals.

McCarter is an avid user of Twitter and has turned to it to challenge corrupt officials to the extent of even calling out the Kenyan government to “stop the thieves.” The hashtag #StopTheThieves has since become a mantra in his tweets. The Nation journalist Aggrey Mutambo described McCarter’s approach as either “tweeting controversy or brutally honest”, and reflected on how the ambassador was embracing digital technology while also taking a leaf out of the book of his predecessors.

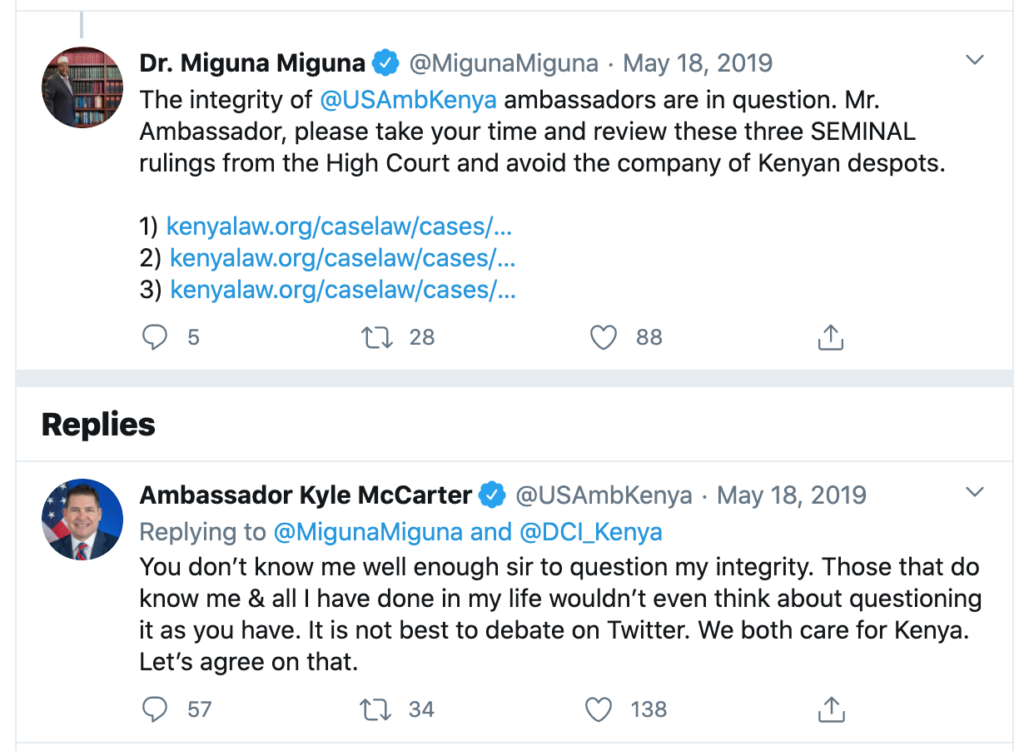

If diplomacy indeed is defined by pure honesty, then McCarter’s tweets regarding corrupt leaders in Kenya were spot on. However, his vocal fight against corruption has not gone down well with some of Kenya’s political elite and has resulted in twars (Twitter wars). In one such tweet, McCarter wrote:

The tweet drew McCarter into a war of words with the leader of the National Resistance Movement, General Miguna Miguna, who questioned the ambassador’s integrity. The ambassador responded to Miguna’s tweets stating that he had the interests of Kenyans above everything else including his personal integrity.

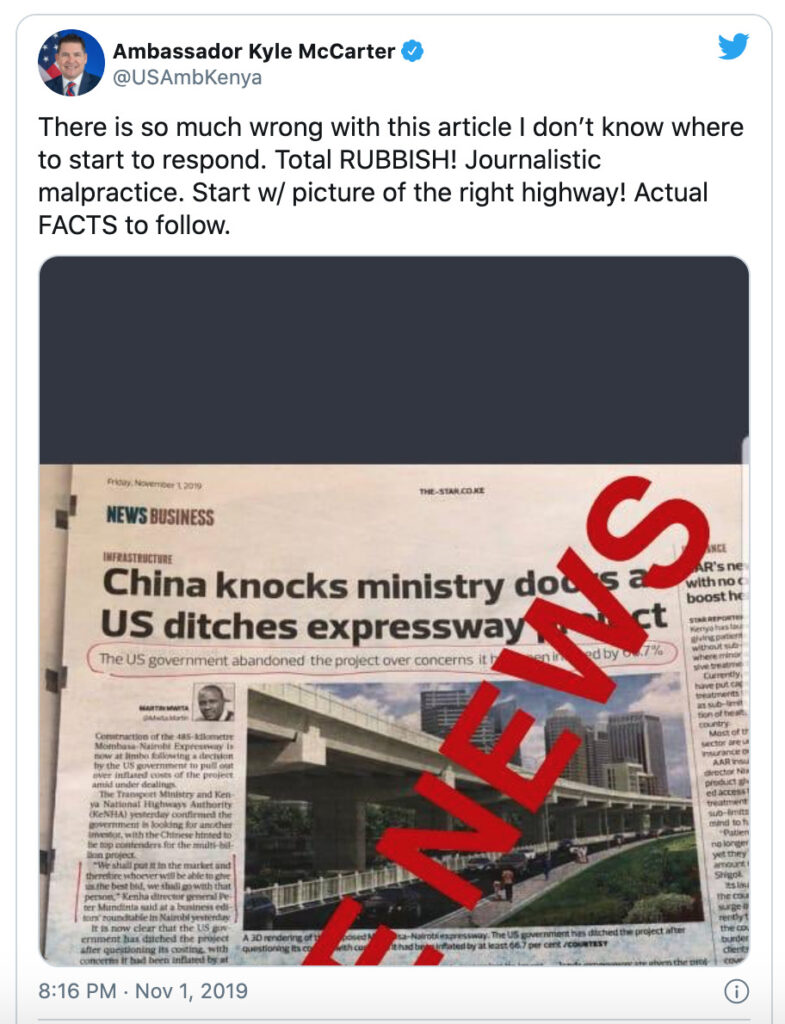

In another instance, The Star published an article on November 1 2019 claiming the US government had ditched the planned Mombasa-Nairobi motorway project, and that the Kenyan government was now looking to Chinese contractors. McCarter rebuffed this, tweeting that the news report was “total rubbish”.

The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School documented responses to McCarter’s in detail. The Chinese embassy in Nairobi responded on Twitter: “China not interested in such rubbish” and published a photo of the newspaper article with the word “Rubbish” stamped across the image. In the same report from the the Belfer Centre, Stephen Chan, a professor of world politics at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, said words like “rubbish” might be common on Twitter, but should not feature in a diplomatic tweet. McCarter did not face repercussions for his tweet, and reiterated that the US was still committed to the motorway project.

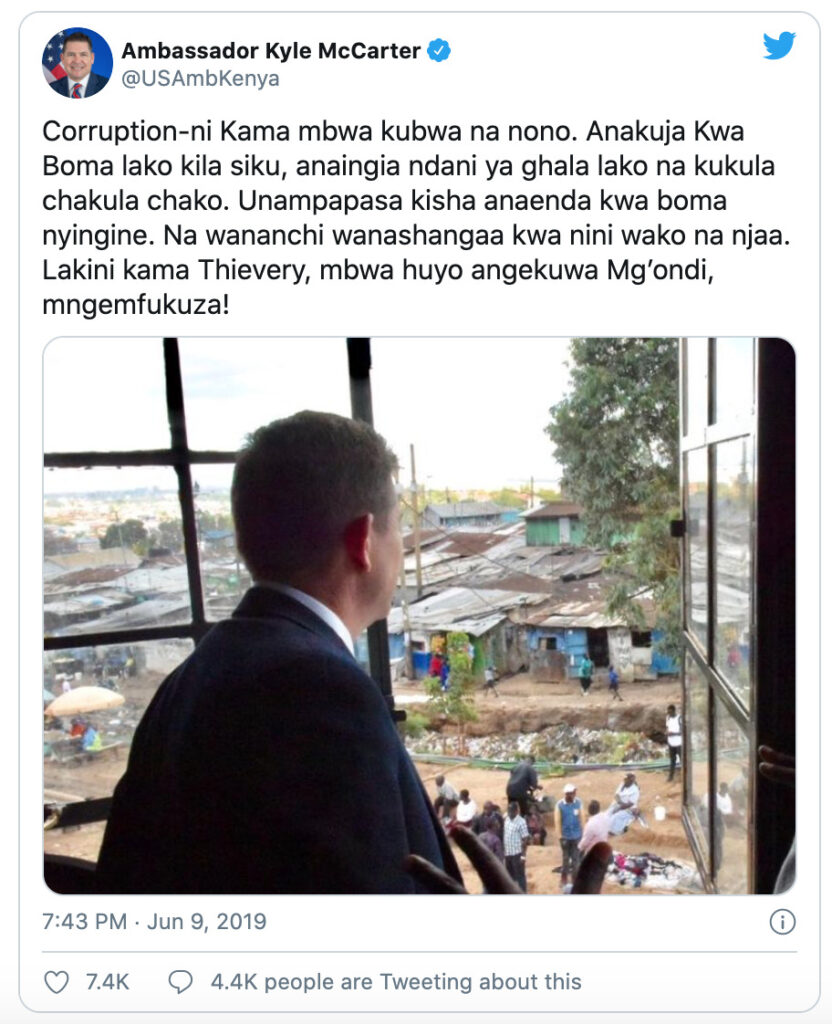

It can be argued that the language used in the digital diplomacy space may not fit in the realm of what constitutes traditional diplomacy. Trump and McCarter are two examples of politicians that have foregone the traditional diplomatic route when they communicate on Twitter. There, sarcasm and satire quickly draw attention to people and therefore are used effectively by diplomats to reach out to to the masses, thereby radiating their soft power influence. Besides also tweeting in English, McCarter has drawn a huge following in Kenya mainly because his tweets are also written in Swahili. This demonstrates an attempt to connect with Kenyans and not just portray the image of a foreign envoy. Below is an example of one of his tweets in Swahili:

Loosely translated, the tweet reads: “Corruption is like a fat dog. It comes to your compound every day, goes to your food store and eats your food. When you chase it, it goes to another person’s compound. Then residents will start wondering why they struck with hunger. However, like thievery, if this dog was a thief, would you have chased it!”

McCarter’s availability on Twitter and his eagerness to engage with Kenyans (and others) on the platform illustrates that Twitter can be a discursive space for diplomats, where communication is reciprocal and informative.

The Mandela tweets

The late Zindzi Mandela was the daughter of apartheid struggle stalwarts, Nelson and Winnie Mandela. She was South Africa’s envoy to Denmark until her recent death in July 2020. Mandela had over 117 000 followers and followed 695 on Twitter.

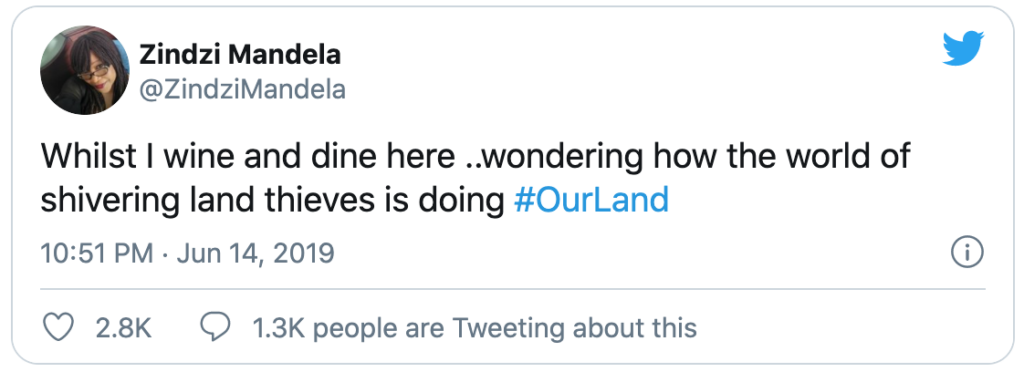

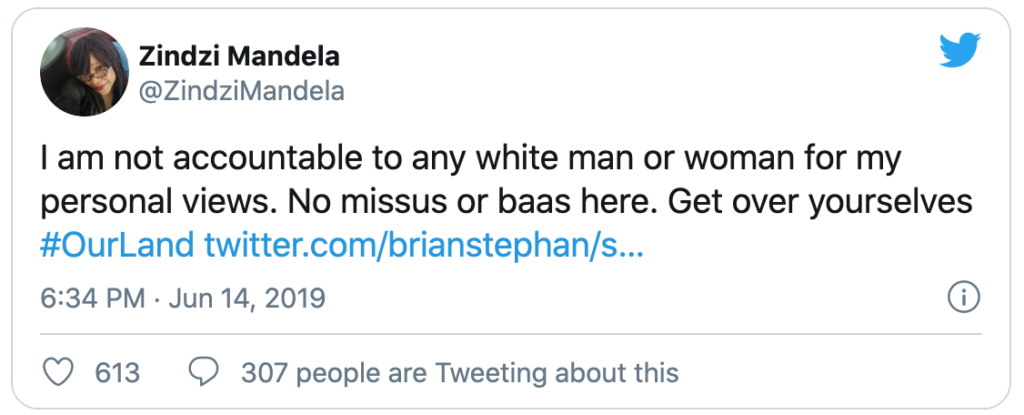

In June 2019, under the handle @ZindziMandela, she drew global attention over tweets that were accompanied by #OurLand. The series of tweets which occurred on mostly the same day read:

Mandela responded to questions regarding her tweets. In one, she said:

The incident garnered widespread media attention in South Africa. #OurLand trended. The IOL News described Mandela’s tweets as having set Twitter ablaze with a series of fiery threads about “white cowards and shivering land thieves”. The Afrikaner lobby group AfriForum submitted a complaint of hate speech to the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) against Mandela for her tweets. With race relations still a controversial issue in South Africa, AfriForum stated that the tweets had a hate-bearing attitude towards white South Africans. AfriForum also focused on the language used in the tweets, describing it as “crude, false and humiliating.” The Citizen reported that the Department of International Relations and Corporation (DIRCO) said it was important to remember that the account was not verified and there was a chance that the tweets were not made by Mandela but by a hacker. The department stated that it would only act in accordance with the social media policy once it had contacted Mandela and investigated the matter, including whether the Twitter account in question belonged to her.

Despite calls from certain sectors of Twitter to get Mandela dismissed from her post as ambassador, other political establishments such as the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) stood in support of Mandela, stating that: “No African child must be suppressed or threatened with losing her job for speaking the truth about the land.”

DIRCO Minister Naledi Pandor reprimanded Mandela for violating the department’s social media policy and labelled the tweets as “undiplomatic and personally insulting.” DIRCO’s social media policy was based on general government policy and bordered on credibility, accuracy, thorough, fair and transparency while encouraging constructive criticism and deliberations in an honest and professional manner at all times.

Mandela’s use of Twitter on a personal or diplomatic level violated the South African government’s social media policy which stipulates guidelines for diplomats and government officials to adhere to. Her use of Twitter displayed its soft power capability in straining domestic and international relations, highlighting the importance of towing the line from a personal and a diplomatic point of view, even when tweeting from a personal Twitter account.

In a visit to Ethiopia in February 2020, US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo said: “South Africa is debating an amendment to permit the expropriation of private property without compensation. That would be disastrous for that economy and most importantly for the South African people. Socialist schemes haven’t economically liberated this continent’s poorest people…. Basic strong rule of law, respect for property rights, regulation that encourages investment. You need to get the basic laws right so that investors can come and invest their capital.”

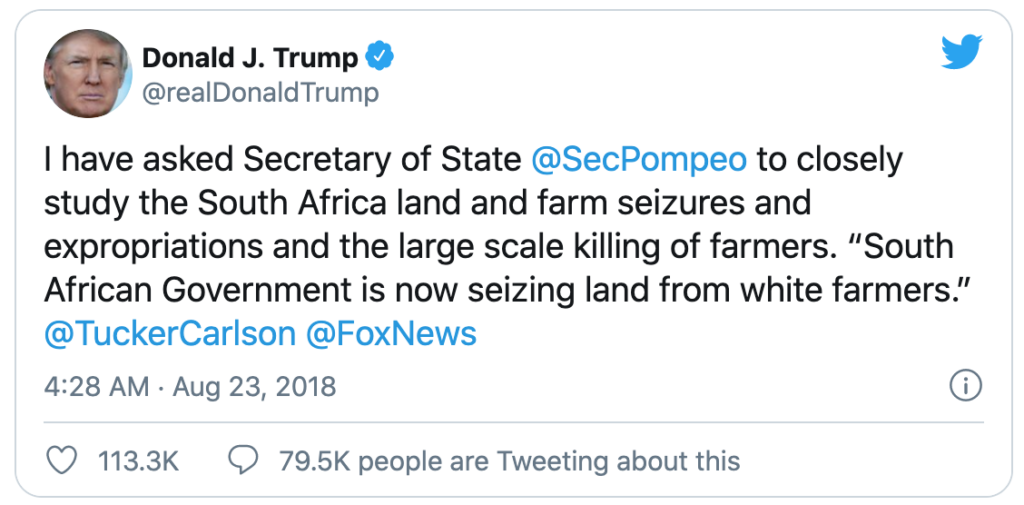

Two years earlier, in August 2018, President Donald Trump tweeted that he had instructed Pompeo to investigate “land and farm seizures” and “killing of farmers” in South Africa. The US has in the past criticised and shown disapproval over any expropriation without compensation in South Africa.

The South African government swiftly put out a response on Twitter, saying: “South Africa totally rejects this narrow perception which only seeks to divide our nation and reminds us of our colonial past.” AfriForum’s legal case against Mandela last year came as no surprise as it had lobbied the US over the deaths of white farmers and had welcomed the above-mentioned tweet from Trump, as reported by the BBC. The controversy over Mandela’s tweets served to highlight ongoing, protracted issues around race, land reform and the legacy of apartheid in South Africa.

Twiplomacy in Africa continues to evolve, albeit with limitations by specific governments and constant government-sanctioned internet shutdowns. The US, through President Donald Trump, has conducted twiplomacy without fear or favour, thereby pushing the frontier of diplomatic efforts on Twitter. African governments still dwell on the traditional form of diplomacy and are yet to embrace the Twittersphere as a reciprocal discursive and democratic space. They ought to harness the soft power capability of social media platforms like Twitter to further diplomatic relations and initiate dialogue between citizens and diplomats in a constructive, democratic manner. However, countries must prioritise infrastructure development for internet connectivity and ensure affordable data pricing in order to make participation in digital diplomacy truly inclusive.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA.

(Main image: Canva)