The release this week of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) special report on global warming of 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels marks a critical point in climate negotiations. Billed in the media as “life changing“. the report illustrates how crossing the ever-nearer threshold of 1.5℃ warming will affect the planet, and how difficult it will be to avoid overshooting this target.

The special report takes a worldwide look at the growing impacts of climate change. But for countries like Botswana and Namibia, which are highly vulnerable to climate stresses, it’s important to understand how surpassing the 1.5℃ global limit will play out at the local level.

For these hot, dry and water-stressed countries, local warming and drying will be greater than the global average. So, even a 1.5°C increase in global temperature will have severe local impacts, ushering in intensified and longer droughts and many more heatwaves. Ironically, when rain does fall, it is expected to be much heavier, increasing the risk of heavy flooding within an overall drying climate.

Botswana and Namibia already know all too well the challenges of droughts and floods. A few years ago, Botswana’s capital city Gaborone was on the brink of running out of water as the country battled its worst drought in 30 years. With its main dam running dry, parts of the city had no reliable water supply for weeks at a time. Neighbouring Namibia has battled with recurrent and devastating droughts and floods in recent years, especially in its northern regions, where most of the population live. In 2017, following four years of drought, heavy rainfall hit, causing flooding. Schools had to shut and people had to relocate. The spread of stagnant water caused a spike in cases of malaria.

With the prospect of worsening droughts, floods and other weather extremes on the horizon, the sooner southern African countries can prepare and implement adaptation strategies the better. The world is warming quickly. The Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C, ideally 1.5°C, by the turn of the century will be extremely challenging. To date, mitigation pledges by nations fall far short of what is needed, with global temperatures on track for a warming of 3.2°C by 2100. Under an increasing emissions trajectory, the 1.5°C threshold could be breached as early as the next decade, and the 2°C mark the decade after. This means there is an urgent need for countries like Botswana and Namibia to prepare and adapt — and do so quickly.

Seemingly small increases in global temperature can have serious local consequences

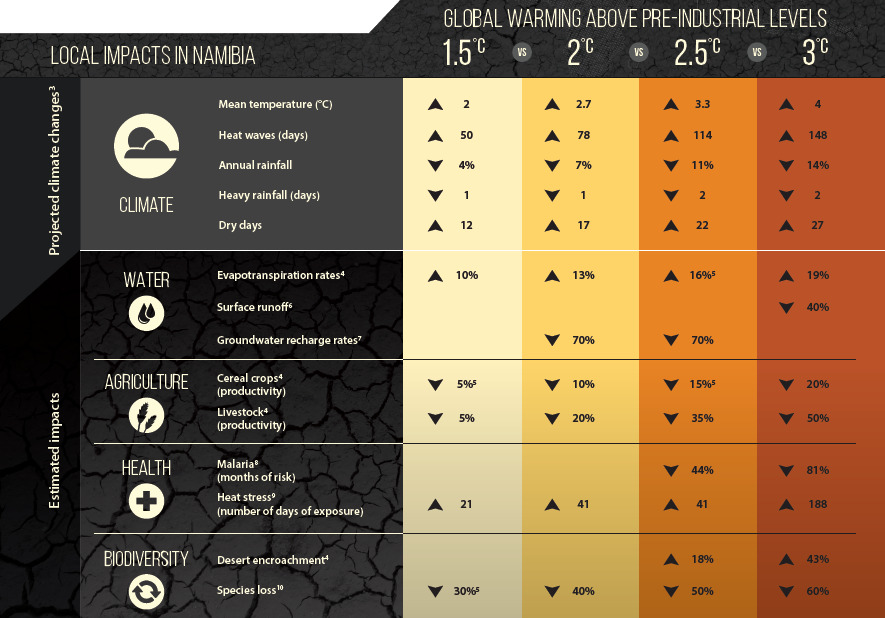

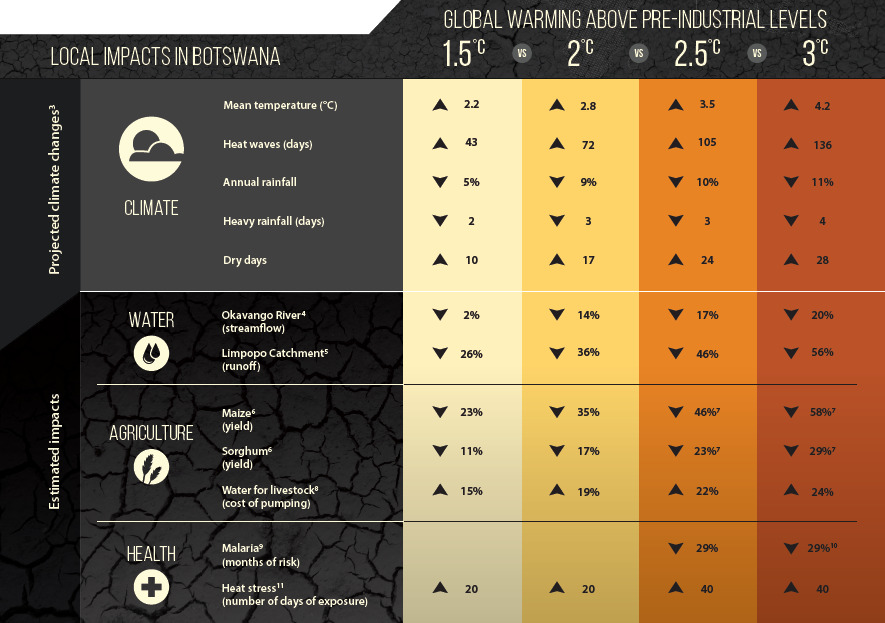

Our analysis of the impacts in Botswana and Namibia of 1.5°C, 2.0°C and higher levels of global warming shows that what seem like small increments in temperature at the global scale can have serious local consequences.

For Botswana and Namibia, 1.5°C of global warming would lead to an average temperature rise above the pre-industrial baseline in each country of 2.2°C and 2.0°C respectively. At 2.0°C global warming, Botswana would experience warming of 2.8°C. Namibia would warm by 2.7°C.

Changes in rainfall are also projected to shift. At 1.5°C of global warming, Botswana would receive 5 percent less annual rainfall, and Namibia 4 percent less. At 2.0°C global warming, annual rainfall in Botswana would drop by 9 percent, with annual rainfall in Namibia dropping by 7 percent.

Both countries would also see an increase in dry days. At global warming of 1.5°C, projections show Botswana having 10 more dry days per year. That number rises to 17 extra dry days at 2.0°C global warming. For Namibia, dry days increase by 12 at global warming of 1.5°C, and by 17 at 2.0°C. The impact of global warming on extreme events is also evident. Both countries can expect roughly 50 more days of heatwaves at 1.5°C global warming, and about 75 more heatwave days at 2.0°C global warming.

The impacts of higher global and local temperatures will be felt in various sectors key to the prosperity of people and economies in Botswana and Namibia. Understanding when different levels of warming will occur, and what these mean for threats to vulnerable sectors like agriculture, health and water, is crucial for adaptation planning and thinking about what must be done, and by when.

In a hotter, drier future there will be less domestic water available. Runoff in Botswana’s Limpopo catchment is projected to decline by 26 percent at 1.5℃ global warming, and by 36 percent at 2.0℃. In Namibia, evapotranspiration rates increase by 10 percent at 1.5℃ global warming and by 13 percent at 2.0℃, leading to reduced river flows and drier soils.

Agriculture is particularly vulnerable, with potential drops in crop yields and increased livestock losses. In Botswana, at 1.5℃ global warming maize yields could drop by over 20 percent. At 2.0℃ warming, yields could slump by 35 percent. Rain-fed agriculture is already marginal across much of the country, and anticipated climate change may well make current agricultural practices unviable at 1.5℃ and above. In Namibia, productivity of cereal crops is expected to drop by 5 percent at 1.5℃ and by 10 percent at 2.0℃.

The impacts of global warming on human health are also essential to consider. Since local temperatures in southern Africa will rise quicker than the global average, heat stress is projected to become an increasingly greater threat. At 1.5℃ of global warming, Namibia and Botswana can expect roughly 20 more days of heat stress exposure in a year. At 2.0℃, in Namibia this doubles to around 40 more days of heat stress exposure.

All of these impacts become even more severe should the 2.0℃ threshold be overshot. For example, at 2.5℃ global warming, Namibia’s groundwater recharge rates could drop by 70 percent and runoff into Botswana’s important Limpopo catchment could slump by almost half. At 3℃ of global warming, projections enter frightening territory: both countries could experience close to 150 extra days of heatwaves in a year.

Urgent action is needed

Global warming of 1.5℃ and higher will add to the climate adaptation challenges Namibia and Botswana already face with the 1.0°C warming experienced to date. The implications of what the near future holds for these countries demand concerted action, both locally and internationally. Leaders from countries such as Botswana and Namibia cannot let-up on the global stage in pushing for nation states to make good on, and further improve, their pledges to cut greenhouse gas emissions in line with the Paris Agreement. As the IPCC 1.5°C report shows, early and decisive action will not only reduce the risks of overshooting the Paris temperature targets, but also slow down the rates of change, making local adaptation easier to roll out.

But, given the lack of ambition in emission reductions so far, and the major energy and land-use transformations that IPCC report claims will be needed, highly exposed countries such as Namibia and Botswana need to anticipate and plan for quite rapid changes in the characteristics of local weather and climate. We need an acceleration in developing adaptation strategies for key vulnerabilities in a way that works for all people and across the economies of these countries. The time for pilot adaptation projects and experiments is over, and the moment to start mainstreaming climate resilience into public, private and community sectors has arrived.

In parallel, governments, scientists and development practitioners need to think longer term, to consider what overshooting the 1.5°C and 2°C targets really means for adaptation, with a view to understanding the limits to adapting current livelihood and economic systems. At some stage, adaptation of these systems may not be enough, and complete transformations to new livelihoods that are suitable in a 2°C+ world may be needed. These transformations are likely to be needed sooner in climate change ‘hotspots’ such as Namibia and Botswana.

This article was first published by our content partner, the Climate & Development Knowledge Network.

(Main image: A man crosses the dried Bokaa Dam with a donkey cart on the outskirts of Gaborone on 14 August 2015 in Botswana. The dam with a capacity of 18.5 million cubic meters was at the time not supplying any drinkable water due to the drought. – Monirul Bhuiyan/AFP/Getty Images)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.