While conducting fieldwork in Benue State, Nigeria in 2017, I was intrigued by a question from one of the young men in our group discussion, who asked: “What is ECOWAS [the Economic Community of West African States] doing at all to resolve farmer-herder conflicts in West Africa?” In my attempt to answer the question, I mentioned the role that ECOWAS had played in ensuring herders’ access to resources in member countries through the enactment of the protocols on Transhumance and Free Movement of Goods and Persons. I explained that, through these protocols, ECOWAS sought to address issues of resource use by herders to avoid violence with farmers. At the end of my explanation, my respondents were not convinced at all and still felt that the regional body had not been forceful in resolving violence/conflicts between farmers and herders. The locals’ depth of knowledge and forthright expression of their frustrations at the inability of national governments and ECOWAS to find solutions to internecine farmer-herder violence was impressive.

The concerns and questions of that youth group remain pertinent today. I have pondered about what ECOWAS had really done or is doing to resolve farmer-herder conflicts in the region myself. One respondent had even asked: are we waiting for Europe or the USA to resolve these conflicts for us? Or we do not see these conflicts as constituting security threats to regional stability? Their questions about ECOWAS’ role in finding solutions to farmer-herder conflicts stem from the politicisation and bias of national governments in tackling these conflicts.

Undeniably, ECOWAS led efforts in the late 1980s and early 1990s to resolve violent conflicts in the Mano-river region (especially in Liberia and Sierra Leon) that threatened the whole sub-region. One can criticise ECOWAS for some lapses during the crises, such as the security lapses of the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG), but overall, the regional body effectively resolved these conflicts and restored stability and democracy in Liberia and Sierra Leone in the early 2000s. ECOMOG was instrumental in bringing peace and stability to war-torn Liberia and the region in general. In the Gambian political crisis during 2016-2017, ECOWAS was instrumental in helping the country transition to peace.

Catalysts for conflict

A background to ECOWAS and the enactments of the protocols on transhumance in 1998 and free movement of persons and services in 1979 are worth discussing. The enactments of these protocols were meant to ensure inter-country trade and access to resources. In particular, the protocol on transhumance was to help solve the large problems faced by nomadic pastoralists in accessing resources such as water, pasture and land in their own countries of origin, especially the Sahelian countries. However, this protocol has not solved the challenge faced by pastoralists in accessing resources. Consequently, violent conflicts have emerged between them and local communities over competition for land, destruction of farms by cattle, killing of cattle and questions of citizenship/belonging.

One cannot lose sight of the impact of climate change on access to resources and its role on conflicts between farmers and herders. Climate change, coupled with population increases in both human and cattle numbers, has led to greater competition for resources. Interestingly, jihadists’ uprisings in Nigeria, Mali and Niger have added to the woes of pastoralists. During my fieldwork, pastoralists in Nigeria noted that banditry activities of Boko Haram terrorists have forced them to move into Southern Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Chad and other West Africa countries. This increased the numbers of cattle in these countries that were already grappling with competition for resources and, thus, exacerbated confrontation and contestation among farmers.

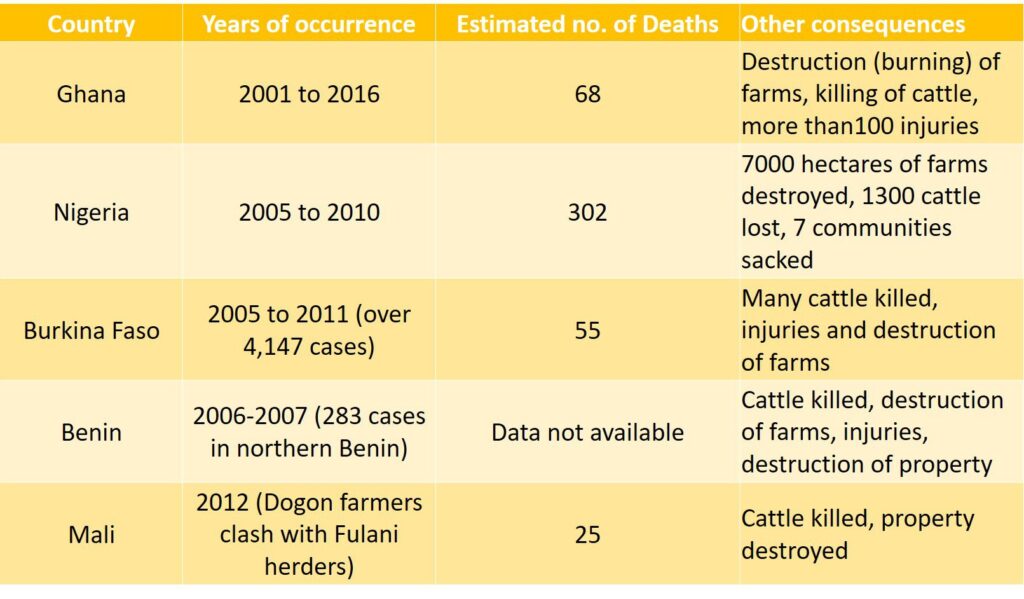

Numbers matter. A cursory reading of local statistics of violent farmer-herder conflicts reveals large numbers (see Table 1 below), although we do not know of many incidences, cases and numbers because they are unreported. According to the 2020 Global Terrorism Index, Fulani extremists were responsible for 26 per cent of terror-related deaths in Nigeria at 325 fatalities. In fact, the 2015 Global Terrorism Index declared them the world’s fourth deadliest militant group of 2014, recording that Fulani militants killed 1229 people in that year.

Table 1: Incidences of Violent Farmer-Herder Conflicts in some West African Countries

In June 2020, 26 people were killed and a village burnt in the Fulani village of Binedama in central Mali. Again, on 24 March 2019, more than 130 Fulani villagers were killed in central Mali when their village was attacked by armed man for supporting jihadist groups. But these clashes in the past have been linked to access to water and land. In 2016 alone, the death toll due to violent clashes between Fulani herders and farmers was estimated at 2500 people. Ghana has also seen sharp rises in violent clashes. On 19 September 2017, violent clashes between farmers and Fulani herders in Brekum, in the Brong-Ahafo region, left 17 people dead, several others injured and many cattle killed. My research in Ghana and Nigeria from 2013 to date reveals that, in almost all parts of these countries, farmer-herder clashes are tragically violent. The number of injuries and fatalities are therefore many, and this deserves greater attention from governments within the sub-region and ECOWAS.

The role of ECOWAS

While I am being critical of ECOWAS and governments of the sub-region, I am optimistic that ECOWAS is capable of finding pragmatic solutions to violent farmer-herder conflicts. One sure way is a revision of the transhumance act to make it operational and reflective of the exigencies of our time. The reluctance of various governments of the sub-region to ensure free passage for herders and clearly reserve resources for them calls for a participatory approach by ECOWAS to involve nations and local people in these decisions. This means a bottom-up approach to finding solutions to the use of resources and conflicts. This approach also requires local communities to participate in finding solutions to conflicts and resource use.

In my various discussions with local people from both Ghana and Nigeria, it became clear that some communities are not opposed to herders’ use of resources in their communities per se. What they are opposed to are the extensive movements of cattle without any confinement, which lead to destruction of crops. To combat this, anti-open grazing and ranching laws and policies are required. Even with the promulgation of ranching laws, there is opposition because local people and herders feel excluded from decision-making regarding these laws. In Benue and Delta States, the enactments of the anti-open grazing laws and establishment of ranches have been opposed by Fulani herders because they said that they were not involved in the decision to enact the law, nor are there even frameworks for implementation of law. In Ghana as well, cattle are reared on extensive basis as there is still no ranching law to regulate the activities of herders. Government efforts to construct cattle ranches in Ghana since 2017 have been opposed by local communities. Herders themselves complain of inadequate pasture and water in these ranches for their cattle.

Land has remained the biggest cause of conflict between farmers and herders. First-comer claims and the citizenship question among herders, in some instances, are at the top of contestations regarding claims to land. As local communities argue, herders do not have automatic right to pasturelands that are idle and unoccupied because these lands have owners. ECOWAS must thoroughly look at this issue at the highest governmental levels to ensure co-existence between the two economic activities that contribute immensely to GDP and employment in the sub-region. This requires zoning lands separately for farmers and herders, especially because herders are often seen as late-comers. Government needs a policy to acquire land banks and leasing out these land banks to pastoralists can be a solution to the problem of land faced by pastoralists, and, therefore, conflicts with farmers as well as a source of income generating activity for people. Once these land banks are established, herders will pay money for their use and other people will grow pasture to feed the cattle, thus providing income and employment to local people.

Finally, ECOWAS needs a commission solely for the resolution of farmer-herder conflicts. Just as we took the resolution of the conflicts in Liberia and Sierra Leone seriously through the formation of ECOMOG and commissions, so must we treat farmer-herder conflicts.

Works cited

Abba, A. B. (2018). The Re-Occurring Farmer/Herder Conflict in Adamawa State: The Absence of Good Governance. Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 2321-8819 and Bolaji, K. A. (2011). Adapting traditional peacemaking principles to contemporary conflicts: The ECOWAS Conflict Prevention Framework. African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review, 1(2), 183-204.

Bukari, K. N. (2017). Farmer-herder relations in Ghana: interplay of environmental change, conflict, cooperation and social networks (PhD dissertation, Faculty of Social Sciences, Georg-August University, Göttingen, Germany).

Bukari, K. N., Sow P. and Scheffran, J. (2018). Cooperation and co-existence between farmers and herders in the midst of violent farmer-herder conflicts in Ghana. African Studies Review, 61(2), 78-102; Benjaminsen, T. A., & Ba, B. (2009). Farmer–herder conflicts, pastoral marginalisation and corruption: a case study from the inland Niger Delta of Mali. The Geographical Journal, 175(1), 71–81.

Bukari, K. N., Bukari, S., Sow, P., & Scheffran, J. (2020). Diversity and multiple drivers of pastoral Fulani migration to Ghana. Nomadic Peoples, 24(1), 4-31.

Cabot C. (2017). Climate Change and Farmer–Herder Conflicts in West Africa. Climate Change, Security Risks and Conflict Reduction in Africa. Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace, Vol 12. Springer, Berlin.

Chikwem, R. (2007). Why ECOMOG is still the best: The success and failure of ECOMOG peace operations. Available: https://dawodu.com/chikwem2.htm (January 26, 2011).

George, J., Adelaja, A., Awokuse, T., & Vaughan, O. (2020). Terrorist attacks, land resource competition, and violent farmer-herder conflicts. Land Use Policy, 102, 105241.

Mbih, R. A. (2020). The politics of farmer–herder conflicts and alternative conflict management in Northwest Cameroon, African Geographical Review, 39:4, 324-344, DOI: 10.1080/19376812.2020.1720755 and Chukwuma, H. K. (2020). Constructing the herder-farmer conflict as (in)security in Nigeria. Africa Security, 13(1), 54–76.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA.