The rollout of oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a pill that prevents infection when taken daily, is not being managed well in parts of Africa.

A handful of African countries – among them South Africa and Kenya – are forging ahead and offering PrEP to people who need it, according to voices at the biennial HIV Research for Prevention conference in Madrid, Spain, from 22 to 25 October.

But other countries appear to either ignore or actively undermine PrEP rollout said Emily Bass, director of strategy and content of AVAC, a New York-based advocacy organisation for people living with HIV.

“My data as a civil society advocate is that in some countries PrEP is being set up to fail,” she told the conference on 23 October.

Data on countries PrEP ambitions is published by PEPFAR, the US programme that funds much of the HIV response in Africa. But for some countries, the ambition in the targets does not match what is being recorded.

For example, Tanzania’s PrEP enrolment target for the financial year ending September 2018 was 12 092 people. But in the first three quarters of that financial year, the country only initiated 2 000 individuals on PrEP.

Tanzania also has no policy framework for PrEP rollout, according to the latest country information from the Global PrEP tracker — an online resource that measures PrEP activity around the world. Nor are there guidelines for who qualifies for PrEP published as yet.

If high PrEP targets aren’t achieved, Bass worries policymakers will use it as evidence that PrEP doesn’t work in their context. “Some of these countries have very ambitious targets because they don’t believe it is going to work,” she told the Madrid conference.

How PrEP works

Daily oral PrEP works by stopping HIV from taking hold and spreading in the body. It has been shown to reduce the risk of acquiring HIV through sex by 90 per cent. The most common form of PrEP is a combination of two anti-HIV medicines, tenofovir and emtricitabine, sold under the name Truvada.

A study presented at the conference pooling data from 46 such pilot projects involving over 10 000 people from all over the world found PrEP to be safe and highly effective in real-world settings.

However, over two-thirds of the 380 000 people enrolled globally on PrEP live in the United States according to the Global PrEP Tracker. Only 100 000 were in Africa, even though the continent has the world’s largest number of new infections.

And PrEP rollout can be politically sensitive. This is beause PrEP services often target high-risk populations such as sex workers and men who have sex with men (MSM). These groups are often marginalised and face difficulties accessing sexual health services. Indeed, homosexuality is illegal in more than half of Africa.

Stalling tactics

To many African policymakers, there is a thin line between providing HIV prevention services for sex workers or MSM, and actively promoting these groups, says Charles Brown, a Ugandan who has worked as a counsellor on HIV prevention trials. “It seems like you are promoting a product for a group that is criminalised. That makes things move slowly,” he says.

In Uganda, Brown says, there was at first a lot of resistance to PrEP. In recent years there has been some progress, but that has been driven by technocrats who fear their superiors’ disapproval should they stick their necks too far out.

As a result, PrEP rollout is happening piecemeal in Uganda, without strong political backing. Brown and others like him promote PrEP through small groups, but this is not the right approach to his mind. “We are pressing the hard for a communication strategy from the health ministry,” he says.

One way in which governments can stall PrEP rollout is by insisting on national ‘demonstration projects’ to investigate whether it works in their local setting. This means PrEP is given out as part of a trial programme, the results from which are analyised and used to inform government policy.

For example, Tanzania embarked on a year-long demonstration study in April this year. An estimated 1.5 Tanzanians lived with HIV in 2017, and around 65 000 people were infected that year.

But many activists believe such demonstration projects are a waste of time. “We’ve seen [PrEP] working in Kenya, in South Africa. What difference will there be in Tanzania?” says Lilian Mwakyosi, a Tanzanian doctor-turned-PrEP advocate.

The access conundrum

Another challenge for PrEP is how to reach one of the most important risk groups for curbing Africa’s HIV infection — adolescent girls and yong women.

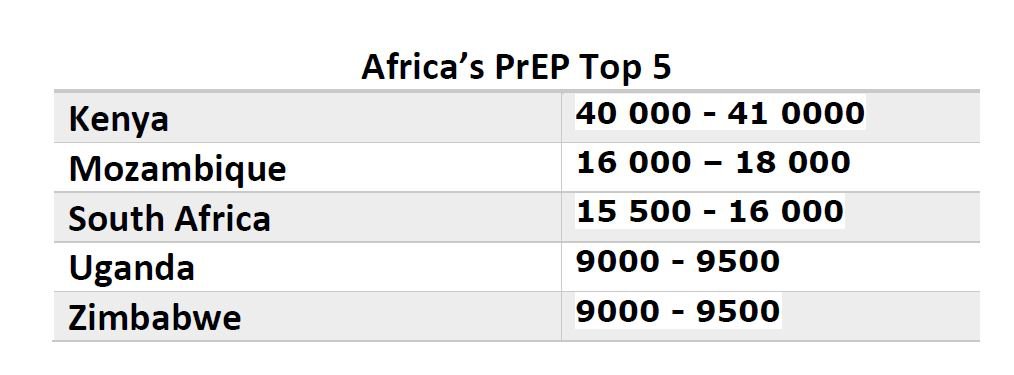

Kenya rolled out PrEP nationwide in May last year. It has the highest enrollment numbers in Africa (see Africa’s PrEP Top 5).

But of that total, half were people living in serodiscordant couples (where one partner is HIV positive and one is not) and a quarter were female sex workers.

Less than 1 per cent were adolescent girls and young women, the Madrid conference heard.

Like with MSM, there are moral and religious objections to providing sex education for young or unmarried girls, let alone target them with tools to help them practice safe sex. This poses a challenge for rolling out PrEP to this group.

Adolescent girls are also one of the hardest groups to get to stay on PrEP, data suggests. In a study of women aged 16-25 in Kenya and South Africa, where the participants knew they were taking PrEP and that it worked, half stopped taking the pill within a month. After three months only a quarter were still taking it.

The researchers who carried out the study, who are based in South Africa, Kenya and the United States, don’t know for sure why so many dropped out. They believe some took PrEP out of curiosity—”something new to be tried”. They admit more research is needed.

Ultimately, people will only ask for PrEP if they know about it, says Gcobisa Madlolo, a young Johannesburg-based mother-of-two who has participated in two PrEP studies to date.

Madlolo — who accepted the 2018 Omololu Falobi Award for HIV advocacy at the Madrid conference — says few South Africans know about PrEP, especially in rural areas where the need might be greatest. And access remains tricky. She has no idea where to source PrEP when her current study ends.

Many HIV scientists, like Sharon Hillier from the University of Pittsburgh in the US, believe the key to solving PrEP’s access problem is to make it more freely available, so people don’t have to see a doctor every time they need it. After all, condoms — which also prevent HIV — can be bought at gas stations. “Prevention should be where people are,” Hillier said.

Travel for this article was covered by a HIVR4P journalism fellowship.

(Main image: Stuart PriceP/AFP/Getty Images)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.