Nhial Tiitmamer, Director of the Environmental and Natural Resources Programme at the Sudd Institute, shares his research into climate-change, migration, and conflict in South Sudan and offers solutions for mediation. This is part of our series on Climate Change and Migration in Africa.

While communal conflict in South Sudan frequently makes headlines, the climate change dimension is rarely invoked, yet it is one of the critical drivers. Climate change is no longer a ticking time bomb: It is already having a deadly impact.

In South Sudan, communities are currently experiencing unprecedented increases in the incidence and magnitude of flooding and drought that have displaced countless people, destroyed lives and torn apart our social fabric. Just last year, for example, more than one million South Sudanese were affected by flooding.

Such climate extremes are taking place within an already fragile political and security environment however, as South Sudan has been devastated by conflict since 2013 and, prior to that, by more than 20 years of a similarly devastating civil war with Sudan. Amidst weak state capacity, a lack of rule of law, and severe underdevelopment, South Sudan’s capacity to mitigate and adapt to extreme weather shocks has ultimately been hindered, resulting in mass migration and frequent conflict.

This nexus between climate change, migration and conflict is barely understood and subsequently given less attention within policy. This op-ed attempts to unpack the key dynamics in this regard, the resultant issues, and possible policy considerations.

The climate change, migration and conflict nexus

Scholarly literature on the climate change-migration-conflict nexus has found that climate change triggers or exacerbates conflicts. This seems to worsen in societies that have weak institutions and weak mechanisms of resolving conflict, in societies that depend on rain-fed agriculture, have poor infrastructure, politically marginalised groups, and ethnically divided citizens. South Sudan meets many of these criteria and our own recent studies at the Sudd Institute have found that conflict in the country frequently occurs after a flood or drought. Specifically, our analysis shows that one single flood event can be associated with about nine conflict incidents in South Sudan.

In South Sudan, many communal conflicts are attributed to competition over natural resources. To gain a better understanding of how this plays out, it is worth considering two case studies: The Sudanese Arab nomads’ migration to South Sudan and the Dinka pastoralists’ migration to the Equatoria Region of South Sudan. The former migration is seasonal while the latter is not, yet both are driven by climatic conditions. The difference however lies in the fact that Sudanese Arabs use dialogue to enter a host territory while Dinka pastoralists do not rely on seeking host permissions. The difference can save lives.

Sudanese Arab migration to South Sudan

Arab nomadic communities of Rizeigat and Misseriya in Sudan have historically engaged in seasonal migration to South Sudan. These communities typically migrate South during the dry season until the rains start around June in the north. Rizeigat are originally from Southern and Eastern Darfur in Sudan and seasonally migrate to Dinka-held Malual areas of Aweil West and Aweil North Counties. The Misseriya of Southern Kordofan seasonally migrate to Dinka-held Malual areas of Aweil East County. The Rizeigat and Misseriya are predominantly Muslim while the Dinka Malual areas are mostly Christian.

“One single flood event can be associated with about nine conflict incidents in South Sudan”.

Moreover after the separation of Sudan into two independent states in 2011, Arab nomads now have to seasonally migrate across international borders, which has posed further challenges to both the migrant and host community.

However, despite the differences between the communities, their strong social, cultural and economic ties have incentivised both to manage migratory conflicts peacefully. What do they do?

With the facilitation of international non-governmental organisations such as AECOM, the Northern Bhar Al Ghazal Peace Commission, and, recently, UNMISS, the communities have set up Joint Border Peace Committees composed of Dinka Malual and the Rizeigat and Misseriya Arabs. The Joint Border Peace Committees work to mobilise communities and inform them about conflict mediation, facilitate the movements of nomads from Sudan to South Sudan and back, investigate and design compensations if an individual is killed, and return abducted children and women, among others. Notably, before the dry season, an annual conference is held to discuss and sign an agreement outlining the conditions of entry and stay in South Sudan. A post-migration conference is also held to agree on the return procedures and to assess the implementation of the pre-migration agreement.

In addition to the Joint Border Peace Committees, communities have set up Joint Chambers of Commerce Committees. These are composed of Arabs and Dinka traders who promote trade and commercial interests in the various regions. Members run what they call peace markets to promote interaction through trade. The Chambers also set rules of lending, intervene when a truck ferrying goods is held on the other side of the border, manage a number of stores and provide rental space. Finally, the Chambers resolve disputes between traders and when they fail, they refer matters to the Joint Peace Committees.

Dinka pastoralists migration to Equatoria, South Sudan

Dinka migration has, much like the Arab nomads’ migration, been triggered by climatic conditions from the Dinkaland in Bor. While some analysts often cite insecurity – such as the Bor Massacre – and an expansionist desire by the Bor Dinka as the drivers of their migration, climate change is often the main driver.

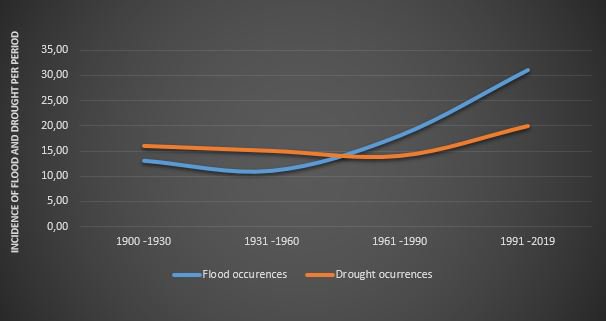

Dinka pastoralists used to migrate seasonally up to Mundari during the dry season but this changed in the early 1960s following a great flood that submerged most of the country’s flood plains in Bhar al Ghazal and Upper Nile for about five years. Since then, the flood frequency has increased (see figure 1) and has for the most part driven cattle herders from Bor into Equatoria in search of better pastures and safety for their livestock. However, because the flood frequency has increased and contributed to widespread disease outbreaks, cattle herders have been unable to return to their home regions and have chosen to stay in Equatoria despite clear and growing tensions between them and host farming communities.

Equatorians complain that the Dinkas have moved in permanently to occupy their land, leading to the destruction of their crops by cattle and growing competition over natural resources. This is justified by the fact that cattle camps have remained semi-permanent in Equatoria beyond Mundariland since the 1960s except for a brief period between 1984 and 1991. Hosts also allege that cattle keepers are supported by the Government and have been provided with weapons to this end. On the other hand, migrant pastoralists say they have to arm themselves to protect their cattle against cattle raiders. The differences between these communities frequently result in conflict. What has gone wrong?

Several issues stand out. Firstly, cattle keepers do not ask for permission to enter the host communities and arrive while armed, raising tensions from the outset. The Misseriya and Rizeigat used to enter Malual areas this way but it often ended in bloodshed. Secondly, it is clear the parties lack a redress mechanism to resolve their migratory issues. However, the parties are unable to do so as they do not recognise each other’s grievances. The cattle keepers ignore the farmers’ grievances and the farmers’ ignore the cattle keepers’ grievances.

To address the situation, in October 2017, President Salva Kiir issued a Republican Order to expatriate Dinka cattle camps from the Equatoria region of South Sudan to their original homelands in Bhar al Ghazal and Upper Nile regions. The Order instructed the military to drive the camps back and to assist vulnerable groups such as women and children with transportation back to their home areas. However, this Order has failed. While some cattle camps moved, some remained behind and the ones that moved returned a few months later. Returnees have cited a myriad of issues but chief among them are floods, disease and insecurity in their home lands. Indeed, this year has already seen the largest influx of cattle camps’ migration into Equatoria triggered by flooding in 2019. Most of the camps have come from Jonglei, Eastern Lakes and Terekka given the wide impact of the flood.

Policy considerations

The main course of action has been to return cattle camps to their original states regardless of the grievances that motivated migration. However, this course of action has not been effective and is not sustainable. Where camps have been driven back, they have simply returned or migrated elsewhere, perpetuating conflict. Moreover, this migration has been to the detriment of the livelihoods of such migrants, as it has been observed that most of the cattle herds in Equatoria are less suited to returning to a different region of the country. Many cattle herds have subsequently succumbed to disease during migration.

The current model of migration therefore encourages conflict and must be redesigned to ensure migration acts as a climate change adaptation measure. In particular, the President’s policy should include addressing the push factors in the states of origin. Policy tools such as building dykes, the vaccination of cattle, the deployment of security forces to reduce cattle raiding and provision of veterinary services can go a long way in creating a sustainable return of cattle camps.

With that said, cattle camps should also be allowed entry to other states if they are running away from a climatic threat, be it drought, flood, or insecurity. Disaster early warning system must be put in place to help determine an impending climate emergency. In these instances, however, pastoralists must seek permission and the host should give consent and show them habitable areas far away from crops with specified duration of stay. The government must disarm both sides and provide security to both the host and the migrant pastoralists. A national or international institution should act as a third party to mediate between the farmers and the pastoralists while a joint committee must be set up to monitor the movement of cattle and to arbitrate in case of a dispute. Joint markets for livestock and agriculture produce should be established to create mutually beneficial ties.

A durable solution must ultimately be designed, one that protects both the migrant and host communities. The government should address push factors in areas of return and repatriate the cattle camps, but in case of a climate disaster, cattle camps should seek permission before they migrate and must comply with local terms and conditions of stay. In essence, these outcomes are by-products of a weak state. South Sudanese must rise above this sectarian and narrow outlook and view the issue of migration from a holistic state-nation building perspective.

(Main image: Residents of Yusuf Batir refugee camp wait in line at a pharmacy in Maban, South Sudan on 27 November 2019. Large areas of eastern South Sudan have been affected by heavy rains in the past months, leaving an estimated 420,000 people displaced from their homes – Alex McBride / AFP via Getty Images)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.

Enjoyed this? Then check out the rest of our Climate Change and Migration in Africa series here.