The Mastercard Foundation’s recent report ‘Secondary Education in Africa: Preparing Youth for the Future of Work’ profiles innovative and promising practices in secondary education reform from across Africa. The Foundation’s Kim Kerr and Mallory Baxter unpack its key findings.

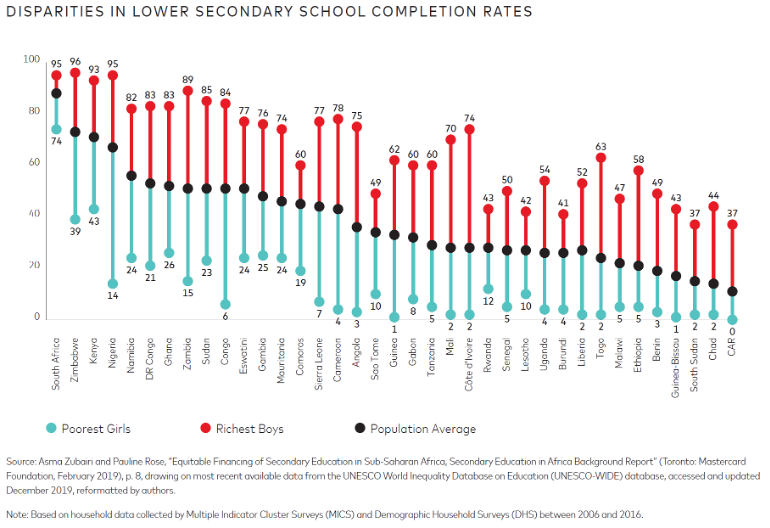

Secondary education is critical to achieving the vision of economic transformation laid out in the African Union’s Agenda 2063. But current indicators suggest that most countries are far from realising this promise. Access, while increasing, remains low compared to other regions and considerable inequities for girls and youth in rural areas persist (see Figure 1). Beyond access, measures of learning and relevance of curricula indicate that youth are not graduating with the skills they need to navigate transitions to work.

The growing youth population and increasing primary completion rates are creating unprecedented demand for secondary education. According to projections by the Education Commission, demand is expected to nearly double over the next 10 years, from 60 million today to 106 million by 2030. As these trends intensify, secondary education will increasingly become the platform to work for youth in Africa.

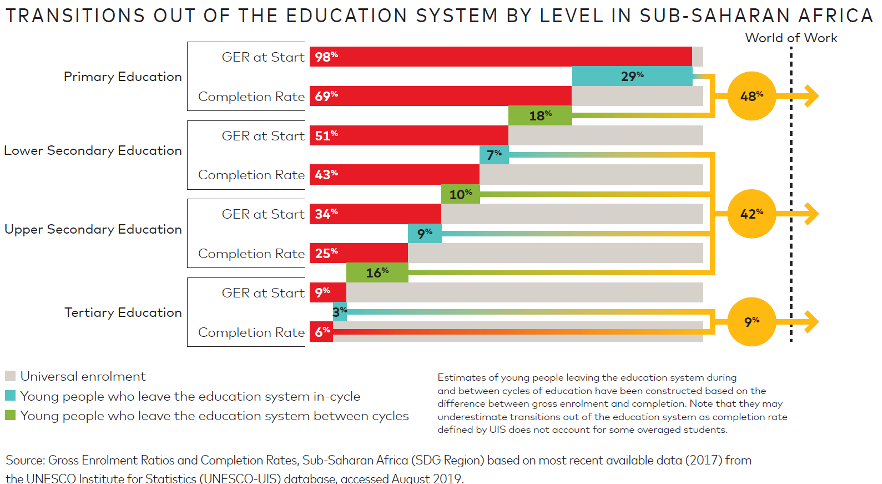

At present, for every 100 students that start primary education, only nine students enter tertiary and only six complete (see Figure 2). Ninety percent of youth transition into work before reaching tertiary education, yet historically, secondary education systems have been designed to meet the needs of the nine instead of the 90. Reimagining secondary education as a platform to work is a paradigm shift – from a pathway to tertiary for a select few, to a mass system capable of meeting the needs and aspirations of a diverse set of learners.

Forces such as digitalisation and automation, climate change, and now the COVID-19 pandemic, are rapidly changing the nature of work, making secondary level skills critical to labour market participation.

Secondary education for all young people contributes to economic growth through higher labour productivity. Youth with relevant skills are better able to engage in complex tasks, adapt to new technologies, improve the quality of products and services produced, and advance innovation. This enhanced productivity is particularly important in the informal sector, where the majority of youth will find jobs for the foreseeable future.

The Mastercard Foundation’s recent report Secondary Education in Africa: Preparing Youth for the Future of Work profiles innovative and promising practices in secondary education reform from across Africa. It is intended to serve as a resource for policy makers and stakeholders in creating accessible, high quality, and relevant secondary education systems.

The report identifies four key areas that can help ensure secondary education systems prepare youth for work.

1. Improving the relevance of curricula to build knowledge and skills

The changing nature of work increases uncertainty and the pace of change, raising the premium on skills that help young people be adaptable, resilient, and creative problem solvers. Skillsets that are critical for secondary school youth include:

- Foundational skills in literacy, numeracy and the language of instruction: These crucial skills lay the ground work for lifelong learning. They are critical to ensuring students are prepared to learn more advanced content and skills. In the short term, given the challenges in learning at primary, remediation at secondary will be required

- 21st century skills: These include skills like critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, communication, and collaboration. They are developed through learner-centred interactive pedagogies and require skilled teachers to deliver.

- Digital skills: Technology is rapidly spreading across all sectors, in both formal and informal workplaces. People without digital skills are at risk of further exclusion as a digital divide emerges.

- STEM skills: Most countries emphasise STEM subjects as part of a broader effort to support science, technology, and innovation. STEM instruction should be made more relevant to young people who do not transition to tertiary and who will apply these skills in their daily life.

- Technical and vocational skills: These skills provide knowledge, practical competencies, and know-how to meet the needs of a growing and diverse labour market.

- Skills for the world of work: Knowledge about career paths, an understanding of workplace requirements, and skills like writing a CV can facilitate the process of securing employment. In addition, most young people will have to create their own work or will be employed in small scale enterprises that require entrepreneurial skills to grow. 21st century skills and a strong grounding in financial literacy and business management skills are essential.

Many African governments have taken steps to foster the development of more relevant skills and knowledge through competency-based curriculum reform or have revised curricula to increase their relevance to national development aspirations. Avoiding curriculum overload in the reform process, as well as making complementary investments in new learning materials and teacher training, are critical for successful reform.

Effective education systems align curriculum, pedagogy and assessment, so that different elements of the system work towards a common set of educational goals. Reforming assessments so they provide insights into student learning, test for the application rather than acquisition of knowledge, and underpin improvements to teaching practices to support learning across the range of skills are vital next steps.

2. Ensuring a highly skilled teaching workforce

It is estimated that over 10 million additional secondary school teachers will be needed by 2030 to meet demand for secondary education on the continent. Due to the rapid expansion of education systems, many teachers lack necessary qualifications. Teachers need stronger subject matter knowledge, as well as training in pedagogies that are shown to impart 21st-century skills.

With competency-based curricula, which depend on teachers skilled in learner-centred and interactive teaching methods, the quality of teaching is even more important than for curricula focused on the acquisition of knowledge. A significant transformation in teacher recruitment and education is therefore needed. Placing high-quality teachers in classrooms is one of the most strategic investments a country can make to enable all students to develop the skills they will need in their working lives.

3. Providing flexible pathways at scale

Many secondary-school-age youth do not transition through their education in a linear manner. Young people who face economic disadvantages often experience significant pressure to leave the education system to seek work and help support their families. Those affected by conflict or climate change often must interrupt their education to seek safety or new livelihoods. Young women face additional pressures that can inhibit their ability to complete school.

Alternative education and training programs to support vulnerable young people should be aligned with mainstream curricula to facilitate pathways back to the formal system. While important in helping to fill a gap, and valuable for their ability to innovate in ways to teach 21st-century skills and other learning approaches, few such alternative programs exist at sufficient scale to accommodate the large numbers of out-of-school youth.

Further, few pathways exist between TVET and general education in most African countries. Once a student has entered a technical track, there are limited opportunities for them to re-enter general secondary school or gain entrance to a non-technical university. That rigidity contributes to the lower status of TVET in the eyes of students and parents. Pathways can be created through “flexible admission procedures and guidance, credit accumulation and transfer, bridging programs and equivalency schemes that are recognized and accredited by relevant authorities”, as Simon Field and Ava Guez suggest in a recent UNESCO publication.

4. Financing with equity

Ensuring that all young people in Sub-Saharan Africa have access to secondary education that prepares them for the future of work will require substantial new resources. It is estimated that a total investment of US$175 billion per year, or 4.5 percent of GDP, is needed between now and 2050 to reach near universal secondary enrolment.

In addition to expanding resources available to education, efforts should be made to find efficiencies, crowd-in other actors, and make more strategic use of official development assistance. Yet, investment at the secondary education level must not be at the expense of primary education, where enrolment has expanded but is still not universal, and serious learning challenges persist.

Efforts to identify efficiencies in current education spending are necessary to free up additional resources. Key areas to unlock resources include improving teacher deployment and utilisation, reducing unit costs of secondary education delivery, addressing high repetition and low learning levels, and improving education system management.

Equity-based funding formulas, targeted need-based scholarships and cash transfers for the poor can remove barriers to secondary education for the most marginalised. These tools must be informed by strong data, policy and community involvement to ensure that funds are targeted to those most in need.

Strengthening and reforming education systems to achieve the promise of quality, relevant education for all is a complex, long-term process requiring sustained commitment and investment. It is an urgent priority and an unprecedented challenge, but it can be done.

For a deeper discussion and in-depth recommendation, please see the full report and other resources on the Mastercard Foundation website here.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.

(Main image: Students study in a library at Waterford Kamhlaba United World College of Southern Africa, a secondary school on 5 August 2013 in Mbabane, Swaziland. – Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images)