In the seventh instalment of the Digital ID Dispatches from Africa series, we have our fourth piece from a country partner who used the CIS Evaluation Framework to examine digital ID in Tanzania. In this article, Patricia Boshe, co-director of the African Law and Technology Institute (AFRILTI), warns that the lack of a data protection framework in Tanzania may introduce risks of exclusion from essential public services, among other risks.

In an age where technology is advancing at an accelerated pace, there is an undeniable need for people to be able to identify themselves securely, on and offline, and have equal and indiscriminate access to services. In fact, Article 6 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights makes ‘legal identity’ a right of every person. It is on this basis that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically goal 16.9, emphasises the need for states to “provide legal identity to all, including birth registration, by 2030”.

In 2014, the World Bank and others launched the Identification for Development (ID4D) initiative to help countries realise the transformational potential of digital identification systems to achieve SDG 16.9. In Africa, this initiative was adopted in the same year under the ‘Identity for All in Africa (ID4Africa)’ campaign; the mission being to help the region realise uniform universal legal identification for all people.

In Tanzania, the idea of providing legal identity to its citizens took root as far back as 1961 when Tanganyika got her independence. The first president of Tanzania, the late Mwl. Julius Kambarage Nyerere, emphasised the need to establish a national identity for the citizens of the new country. Unfortunately, due to financial and other capacity constraints, this ‘dream’ wasn’t realised even after parliament enacted the Registration and Identification of Persons Act in 1986. The law only came into force 25 years later after being published in the Government Gazette (Notice No.257A of 2011), made possible by the establishment of the National Identification Authority (NIDA) in 2008 by presidential mandate.

“Making NIDA IDs exclusive may not be a problem if the administrative and regulatory framework is sufficient to ensure no one is excluded from accessing civic services and that ID pertaining rights are protected.”

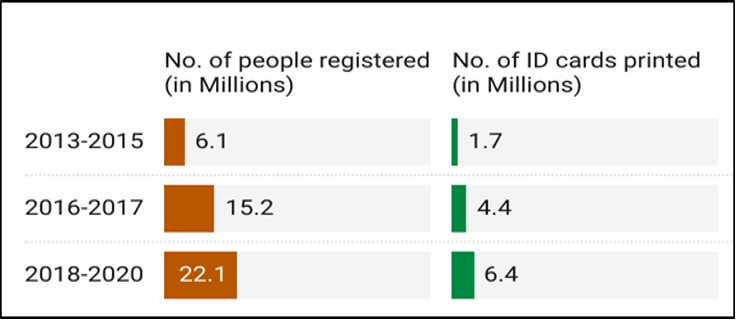

Registration of citizens began in 2013, with approximately 6.5 million residents from seven regions getting registered over two years. However, only 40% of registered residents received their national ID cards. In 2016, the first batch of national IDs were handed out. Unfortunately, the quality of the ID cards raised concerns, especially the illegible signatures, making most of the IDs unacceptable by several financial providers. As a result, the president fired the director-general of the National Identification Authority (NIDA) and the new acting director ordered a massive recall of over two million ID cards. The bottom line is that the overall rate of registrations and issuance of cards was slower than expected.

Regardless of these hiccups, Tanzania still envisions that the NIDA ID would eventually be used as exclusive IDs to identify citizens and to access civic services. Currently most, if not all, public institutions have moved to make the National ID or NINs (as the NIDA ID is commonly referred to) as primary/mandatory requirement for identification for service provision, including institutions like the Higher Education Loans Board, the Tax Revenue Authority, Business Registration, Licensing Authority and the Government Recruitment Agency. This means, for example, that without a NIN students cannot get loans, one cannot apply for government employment, pay tax or register a business.

The same tide is seen in the private sector. It began with SIM card registration in 2009 and is now moving to financial institutions. In the case of SIM cards, one cannot register a SIM card unless the biometric information collected is verified against the NIDA database. Hence, the SIM card database is in effect linked to the NIDA database. If a SIM is not registered against the NIDA ID, it is deactivated. This has created a lot of havoc with people fearing being ‘locked out’ of their SIMs.

In Tanzania, having a locked SIM means more than just being denied access to communications; it affects financial transactions. SIMs are not only connected to personal bank accounts, they are also ‘mini personal banks’. People save, send and receive money via their SIMs. It has become a convenient means used even by people with no conventional bank accounts.

I, for one, experienced SIM deactivation. Although I had the NIDA card, that was not sufficient to keep my SIM active. I was still required to physically report to the service provider to give my fingerprints for verification with the NIDA database. Since I was abroad at the time, my SIM was locked. I could no longer use my SIM to communicate or access my mobile money. Note that at the time only about 22 million of 80 million eligible people were registered by NIDA, and only 6.2 million NIDA cards were printed. This meant that about 58 million people had not yet received their NINs to support their SIM registration. See the table below.

Lack of legal identity could hinder individual access to basic social services but improperly regulated ID systems could have far more negative effects on individuals. If such systems fail to address pertinent technological and social aspects, it may lead to the exclusion of certain population groups. Since the ultimate objective of ID systems is to give people legal identity to allow them access to civic services and exercise individual rights, governments are expected to uphold and protect those rights, moreso, when a country such as Tanzania declares that the national ID is to become the only official ID document, as reported by the East African newspaper in 2015.

Making NIDA IDs exclusive may not be a problem if the administrative and regulatory framework is sufficient to ensure no one is excluded from accessing civic services and that ID pertaining rights are protected. These rights can be summarised in four key Ps:

- Privacy: people can control their identity and what data is shared and with whom;

- Portability: people can access and confirm their identity anywhere they are through multiple methods;

- Persistence: the identification lives with the person from life to death; and

- Personal: the identification is unique to one single person.

So far, the digital ID framework in Tanzania poses a significant threat to personal privacy and the protection of personal data (there is no data protection or regulatory oversight), and potentially abets social exclusion.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA.

(Main image: People waitin a line at the National Identification Authority (NIDA) office to register for a national identity card which requires for biometric mobile phone SIM card registration in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on 14 January 2020. – Ericky Boniphace/AFP via Getty Images)