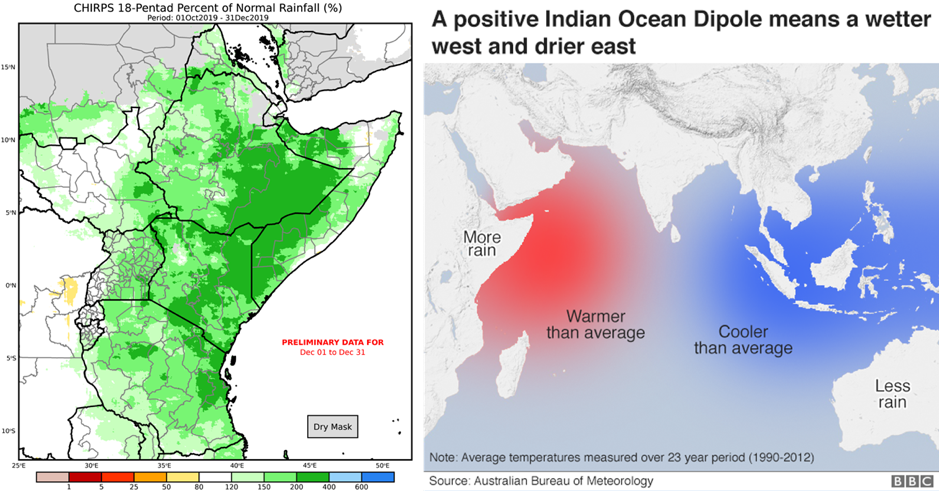

The 2019 Eastern African short rains (October-December) was one of the wettest in recent decades, with many places seeing more than double the typical amount of rainfall for the season. The seasonal forecast from the 53rd Greater Horn of Africa Climate Outlook Forum (GHACOF) did indeed note that above average rainfall was most likely.

The forecast skill was helped considerably by the presence of a strong positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), i.e. particularly warm waters in the western Indian Ocean known to enhance rainfall during the regional short rains.

This same oceanic feature has contributed to the dry conditions in Australia, conducive for the devastating wildfires seen. Despite the reasonable seasonal forecast for East Africa, the rainfall has reportedly led to over 200 deaths and affected nearly 3 million people in the region, showing the need to increase resilience to such extreme weather events.

The event itself also brings into question the responsibility humans have for the extreme weather, i.e. what affect might climate change have had, and what effect might it have in future, on the prevalence of such events?

It is generally impossible to say whether any individual event is due to climate change, but it is possible to say how climate change will alter the probability of an event. It is rather like a loaded dice: you cannot say that any particular six occurred because the dice was loaded, but you can say that the chance of a six was, for example, doubled.

Recent work has used climate models to look at the relationship between the frequency of strong positive IOD events and climate change.

The study concludes that under a global average warming of 1.5°C (since pre-industrial times), a key target of the United Nations Paris Agreement on climate action, such IOD events may occur twice as often. This conclusion implies that the 1°C of global warming already being experienced (since pre-industrial times) could have substantially increased the probability of extremely positive IOD events, like that which occurred during the 2019 short rains.

Since the prospect of limiting global warming to even 1.5°C is seen as hugely optimistic at this stage, Eastern Africa must be aware that events such as the short rains of 2019 may become even more frequent and governments should look to prepare for such intense climate fluctuations in the future.

The study further strengthens the body of evidence supporting significant efforts to not allow temperatures to go beyond 1.5°C. If this target can be achieved then projections suggest the risk of strong positive IOD events reduces by 25% compared to a 2°C warming.

The rate of recent warming of the western Indian Ocean is one of the fastest of any tropical ocean over the last century, and climate models project that continuation of these higher rates of warming should be expected under climate change. The cause is the emission of greenhouse gases by humans.

Higher rates of warming in the western Indian Ocean shift the sea surface temperature pattern towards the positive IOD state. Recent work from the Future Climate for Africa programme (including from HyCRISTAL) has shown that climate change can also increase the intensity of rain in storms over Africa because global warming increases the moisture content of the atmosphere.

Therefore, for any given strength of IOD, rainfall in the future is expected to come from more intense events than in the present-day. It should be noted that climate models tend to overestimate the strength of the IOD but measures can be taken to correct the overestimation in order to gain useful information about IOD projections. Since there is strong agreement across climate models regarding changing Indian Ocean temperatures, consideration must be given to the potential impacts within the decision-making process.

Within that process it is important to consider the increased risk of extreme rain events within the context of changing trends in average rain accumulations.

While most climate model projections show increased rainfall during the short rains under future climate change, consistent with the warming western Indian Ocean, some climate model projections suggest that it is possible that average rainfall could decrease during the East African short rains in future.

This combination of needing to prepare for more intense rainfall events and more extreme seasons due to more strong IODs and the uncertainty regarding changes in total rainfall accumulations poses a significant challenge to decision-makers, but one which can’t be ignored.

The HyCRISTAL project is assisting with the challenge by providing a fresh look at existing climate information, as well as using models at the frontier of climate science to give new insights. This work has been brought together for decision-makers in the form of narratives that lay out possible futures to consider in urban and rural areas. Within HyCRISTAL, pilot studies are working to integrate such long term information on climate change into planning and decision-making in East Africa.

- For more information read the Scientific Understanding of East African climate change from the HyCRISTAL project.

This article was written by HyCRISTAL researchers Declan Finney (University of Leeds), John Marsham (University of Leeds), Caroline Wainwright (University of Reading) and Dave Rowell (UK Met Office). It was originally published by our content partner, Future Climate for Africa.

(Main image: An aerial view shows a submerged village in Gaarsen, Tana River district, about 500 kilometres southwest of Nairobi, taken 22 December 2006 where at least 18000 people were displaced by flooding. – Tony Karumba/AFP via Getty Images)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.